The Screen: Product of the Hyperreality Machine

by Dr. Oleg Maltsev

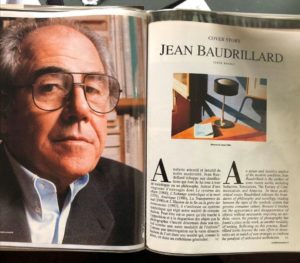

Jean Baudrillard considered different pressing phenomena and introduced many concepts to describe today’s world of hyperreality – among them the screen, seduction, simulacra and simulations, and the silent majority. All of these are determinate elements that, when woven together, constitute hyperreality, and it is the machine of hyperreality that generates these elements. It is hyperreality that transforms people into a mass, a screened out, silent majority, as theorized by Baudrillard. This article focuses on the screen as one of the phenomena generated by the machine of hyperreality. It describes the stages through which it is formed and examines how it affects human life.

In my work as a criminologist and sociologist working with the Expeditionary Corps of the Memory Institute, I have led over 40 field studies and investigations of case studies across four continents. In recent research on the Sicilian mafia conducted in Italy, the expeditionary group focused on the methodology involved in the upbringing of the mafia leader, the Capo. Before starting the study, and after studying the work of other scholars, we came to the conclusion that no-one had done such a study before. Previous scholars have described particular mafia bosses and their biographies, but we were interested in exploring the intermediate stages through which someone passes en route to becoming a Capo. The real-world mafia has little in common with representations in cinema and literature.

This new study on the process of becoming a Capo required a research methodology that had not previously existed. For this purpose we took the “language” of European mysticism and that of Baudrillard and compared them, and came to the conclusion that the essence of “Baudrillard’s language” corresponds completely with the language of European mysticism. This analysis has been presented in detail in my earlier work, “Maestro: The Last Prophet of Europe”. Thanks to the methodology gleaned from Baudrillard, we were able to assemble a complete working model of the machine of hyperreality, the elements of which Baudrillard described in his writings. The results of this research form the basis of my next book on Baudrillard’s system, Ownerless Herd. “Ownerless Herd” is another name for what Baudrillard calls the “masses”, the “silent majority”, or the “screened out. This book is about the world order that we live in and is designed to provide an analysis of the real functioning of the global machine of hyperreality, including an analysis of the elements of this machine and their impact on the opportunities of each person. The book will also provide in-depth analysis of information distortion methods and models that explain the nature of many of today’s conflicts, be they geopolitical conflicts or an everyday conflict between two people. This straightforward and practical book will show how different mechanisms and elements that are an integral part of our societies create hyperreality and turn people into an “ownerless herd”, in other words, into idiots.

Contents of the book:

- Ownerless herd

- Ode to Hyperreality

- Baudrillard’s Hypothesis of Hyperreality (Machine and Fate)

- Who are we dealing with?

- Theory and Practice of Conflict

- Simulation and Simulacra

- Denial of Memory

- Screen and Hyperreality (First Approach to Hyperreality)

- Seduction

- Working with the Machine of Hyperreality

- Expertise as an Inherent Part of the Machine of Hyperreality

- Everything (even pregnancy) is a Reflection of the Instinct for Power

- Transformer (Two-side Group Technology). Blogger (key and insight)

- You Are Given to Yourselves to Be Destroyed

- The Machine of Hyperreality: Assembling

⁃ Generator – Conflict

⁃ Generator – Simulacra and Simulation

⁃ Blocker – Denial of Memory

⁃ Staging – Seduction

⁃ Reducer – Expertise

⁃ Transformer – Media and Global Network

⁃ Stabilizer – Adaptability and Maladaptability

- Technological Efficiency and Hyperreality

In the book “Maestro: The Last Prophet of Europe,” I offered a construction of Baudrillard’s philosophy which is reflected in a model which consists of three parts:

- The world in which we live;

- A kind of prism (or screen) through which we look at this world;

- Unexplained mystical phenomena.

The everyday experience of the world does not accord with the world itself, but rather, is filtered through ideological ways of relating to it. These ways of relating are themselves co-constituted with the social machine they represent, which today is the machine of hyperreality. The screen or prism does not appear out of thin air, and there are very concrete reasons for its existence. It is probably unnecessary to tell most readers that the civilized age is oversaturated with information. Today there is a totally imaginary belief that we can find all kinds of information on Wikipedia, Google, etc. These sites provide unprecedented accumulations of real and purported facts, often beyond capabilities to process for a modern man. But it was not for nothing that Baudrillard said, “We are in a world in which there is more and more information and less and less meaning.” Despite the abundance of information, people are not able to find knowledge that would help to acquire the skills, tactics and logic of winning, that would help achieve results. People are surrounded by information, but are often unable to tell the authentic from the dissimulated, to filter the biases of sources, or to make use of data in creating meaningful analyses of the world. The more facts we accumulate, the more stupid we become.

The everyday experience of the world does not accord with the world itself, but rather, is filtered through ideological ways of relating to it. These ways of relating are themselves co-constituted with the social machine they represent, which today is the machine of hyperreality. The screen or prism does not appear out of thin air, and there are very concrete reasons for its existence. It is probably unnecessary to tell most readers that the civilized age is oversaturated with information. Today there is a totally imaginary belief that we can find all kinds of information on Wikipedia, Google, etc. These sites provide unprecedented accumulations of real and purported facts, often beyond capabilities to process for a modern man. But it was not for nothing that Baudrillard said, “We are in a world in which there is more and more information and less and less meaning.” Despite the abundance of information, people are not able to find knowledge that would help to acquire the skills, tactics and logic of winning, that would help achieve results. People are surrounded by information, but are often unable to tell the authentic from the dissimulated, to filter the biases of sources, or to make use of data in creating meaningful analyses of the world. The more facts we accumulate, the more stupid we become.

One of the reasons for this state of affairs is the rejection of historicism. By this, I do not mean a particular philosophy such as a teleology of history. I mean a broad awareness of the place of the present in a wider, and changing, historical context, a context in which causal, structural, and intentional forces operate. Today we are caught in an eternal present, a situation of “present shock” in which the sense of past and future are lost. Historicism is what a healthy human mind relies on to situate the wider social environment, and which contributes to an identification of one’s self. Modern man is essentially devoid of historicism, and the word itself does not evoke any associations for most people.

We tend all too easily to forget that our reality comes to us through the media, the tragic events of the past included. This means that it is too late to verify and understand them historically, for precisely what characterizes our century’s end is the fact that the tools of historical intelligibility have disappeared. History had to be understood while there still was history. (Baudrillard, J. (2014). Screened Out.)

And is there really any possibility of discovering something in cyberspace? The Internet merely simulates a free mental space, a space of freedom and discovery. In fact, it merely offers a multiple, but conventional, space, in which the operator interacts with known elements, pre-existent sites, established codes. Nothing exists beyond these search parameters. Every question has its anticipated response. (Baudrillard, J. (2014). Screened Out.)

Instead of historicism, modernity offers a kind of information swamp, a seething mass of data in which people boil. It only takes a little critical thinking to find out that that information swamp is an accumulation of distortions, contradictions, half-truths, and misinformation. Everything is filtered through the machine of hyperreality which constitutes the present, with the result that the past and future cannot be seen clearly. The simplest example of the distorted view of history provided by the information swamp is the widespread view of the Middle Ages. Today, most people believe that medieval Europeans were uneducated, dirty, unenlightened, and vastly inferior to the people of today in their science, technology, and philosophy. Yet this is in sharp discrepancy with the surviving material culture of what these supposedly uneducated people were able to build. Medieval architecture continues to fascinate modern observers and attracts tourists from all over the world. These wonders of European mysticism were created by the same “uneducated” persons denounced by modernity. If one does not study historical processes, does not ask such questions, the rejection of historicism has consequences. In order to explain this in the modern context, here is a heuristic model of the pyramid that shapes public opinion (according to Prof. Massimo Introvigne):

There are five levels in this pyramid from top to bottom: government, academics, experts, media, and social media. Most information flows hierarchically down the pyramid, or in more complex cases, is extrapolated upwards and then fed back downwards to those who were its initial source. Top-down information flows down this pyramid directly to the masses. Consumers devour this information and so they form a certain screen, a way of seeing and relating. And when two people look at each other, they look through the prism of this pyramid. In reality, the frame is being passed down from above in the majority of cases. There are often invisible hierarchies at work, including legal and other contestations regarding the regulation of the supply of information. Different decision making fractions use the same top-down process for different purposes. Often, these purposes are polarized, with certain elite fractions trying to monopolize authority in a given field, so as to capture rents or influence. The result of this process is that the screens available do little to aid understanding of a complex reality, and do not even provide an overarching ideological unity. The screen does not reflect reality, but generates conflict. Because two people look at the same situation through two different prisms, they see it very differently, and in the logic of hyperreality, the resultant conflicts of interests, opinions, and so forth, often become insoluble. They are determined at the level of framing, and are not subject to mutual understanding, mutually recognised evidence, or common forms of reasoning. On a larger scale, this conflict of screens leads to the recurrence of violence, war, and terrorism, as Baudrillard argued. On top of that people are so caught in a hyperreal media bubble that they cannot assess information except in a manner which reproduces existing biases.

The screen is not just a way of explaining things, in the manner of a scientific or philosophical theory. The screen allows one not to think. It provides pre-formed answers to all questions, and allows a properly conditioned ideological subject to live in dangerous, changing social conditions without feeling stressed. The screen thus meets an important emotional need: human beings do not like to feel pressure and stress, and in conditions like those today, excessive stress can be debilitating. Someone who foregoes the use of the screen to avoid doubt and worry may collapse under the strain. Yet this coping mechanism, useful for individuals, is devastating on a social scale. The more the two sides in a conflict are given simple answers and means to avoid thinking, the further their points of view drift apart, and the more fear and hatred arise between them. Because of this, people find themselves caught in daily arguments and conflicts, without having any awareness of what the grounds of the conflict are: they feel they are simply coming across others who are absurdly irrational, ill-informed, and morally outrageous. In reality, this impression arises because one is arguing with someone subjected to a different screen, and neither oneself nor the adversary is able to see either of the screens at work or to compare them to reality.

90% of the decisions in life are made on the basis of the information which is screened, and this situation in turn generates most of the problems on all layers of society. People think they are making free and rational decisions, but in fact, the screening process predetermines many of the choices or restrains them within given parameters. A person cannot give up the screen because he knows nothing about it. The screen today starts in childhood, with parental norms and commands which the child is not to question on pain of punishment. The associated beliefs are taken as true. The role of the parent passes smoothly into that of school, of the peer-group, and later of various kinds of online “experts” on sites like YouTube. People never get outside the screen in which they are raised, even though at the same time, there is some pluralism of opinion. In principle, each person can look at a situation or phenomenon the way they want, and everyone learns about democracy, rights, free speech, differences of opinion, etc. However, none of this stops the screening of worldviews, and people continue to shape their perceptions of the world on the basis of secondary, half-true or outright false data (“someone told me…”). The context of free opinions is mobilized in the service of screening, operating as a cover for the right never to doubt one’s screen. This situation has spread to all aspects of social life: not just everyday political and lifestyle discussions, but also business, economics, politics, international relations, science, technology, and so on.

The screen brings with it another danger: a consensus based on сonsent. It is the constant attempt to arrive at a consensus on the basis of the consequence of the screen, of screened vision, which leads people into subjective conditions similar to psychiatric disorders. If people continually come to consensus and agree that we now call a red object green, or that green and red are the same, then this is how everyone will become color-blind. All too often, consensus on surface slogans and concepts conceals a vagueness and even a polarized view of the content of these words. What have we gained through consensus? Science, among other things, has become a kind of simulation. Without clear conceptual distinctions, nothing can be tested, confirmed, or refuted. Instead, we get an illusion, a consensus-by-diktat in which the distinction is rhetorically denied or occluded. We might think, for example, that a pen has become a rhinoceros – but this is simply an illusion, a change in conventional language which is mistaken for a change in reality. Today, accumulations of these kinds of consensus illusions are piling up as extended constructs known as simulations. Because people keep agreeing, they keep looking for causal connections between all these incoherent objects. The result is that certain of these constructs seem to society to have been “proven”, and in a sense have been, since the posited objects observably relate – but the resultant knowledge is too imprecise to be scientific.

For example, in psychology, people have supposedly been able to prove to each other than human beings exist simply at a neurophysiological level. The mind is the brain, and the brain is observable by scientists. This belief is certainly not true: there is also the level of the experienced psyche, and there is also a spiritual component, the experience of qualia, of an “I”, etc. But if you take the vast majority of psychologists in the world today, they will only reach the anthropological and neurophysiological level in their conversation. And as soon as they start talking about psychology, if not all of them, then very many will say that it is too ephemeral and not quite scientific… and that a human being has no “I” as such. Today we clearly see that very many scientists approach the question in the way described above. Jean Baudrillard, as always, was to the point, in his description of what is happening in the modern world:

“But the trap with these plural identities, these multiple existences, this devolution on to ‘intelligent machines’—dice machines as well as the machines of the networks — is that once the general equivalent has disappeared, all the new possibilities are equivalent to one another and hence cancel each other out in a general indifference. Equivalence is still there, but it is no longer the equivalence of an agency at the top (the ego); it is the equivalence of all the little egos ‘liberated’ by its disappearance.” (Baudrillard, J. (2013). The Intelligence of Evil: or, The Lucidity Pact (Bloomsbury Revelations) (Reprint ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.)

The motivation for the consensus is profit. Illusory consensus offers both an illusory profit, an illusion of social consensus, and a real profit, an avoidance of stress and doubt. The pseudo-consensus appears to be advantageous for everyone. That is, the screen allows one to think profitably – in the way that is convenient for the person at a certain moment in time. At the same time, the screen allows (or even compels) someone to change their opinion as the situation changes, since the information they are reacting to also changes. A person thus becomes “multifaceted”, “flexible”, because the screen determines the perceived reality towards which one orients. The screen gives a lot of information, and a person can choose the one that is beneficial to him and ignore the one that is not. A certain kind of psychiatric madness, a pattern of self-reproducing delusions and quasi-hallucinated realities, thus becomes a general human condition. There is no longer a reality-check on wishful thinking or on compulsive moral imperatives. That is, the danger of the screen is that it leads to the destabilization of the human psyche.

The result is not a disappearance of reality, but a complete lack of fit between perceived reality and the environment in which people operate – or more precisely, between the social environment (simulation, hyperreality) and the physical, natural, bodily, spiritual, and other realities which are not part of hyperreality. Hyperreal thinking makes it easy to say that black is white, or that black and white are both gray, that real differences do not exist. This takes away the function of concepts in sorting objects in the world. When someone says that black is white, they lose their entire system of orientation in the world. We might say, for instance, that someone chooses a map of New York, because this map seems the most profitable, the most appealing or aesthetically pleasing, the most strategically useful, or the map which is used by a person’s peer-group. Using this map of New York, the person travels through Paris – taking the map as a guide. Undoubtedly, very soon, such a person will have an accident or become completely lost. This happens all the time today, metaphorically speaking, as people use conceptual toolkits chosen for completely the wrong reasons, and run up against realities which do not fit their models.

In hyperreality, we can continue, the person using the wrong map gets used to it, and does it all the time, is constantly lost, and gets into accidents of all kinds all the time. Yet they never question the map (which, after all, is a good enough map for some purposes). This is taken to be “just life”, or proof of the general inadequacy of maps, or explained away on the basis of other ad hoc theories forming part of their worldview. Perhaps the person becomes convinced that they themselves are inherently flawed and this is why they have accidents. Perhaps they become convinced that some structural force or invisible adversary is sabotaging their journeys over and over. In fact, the screen is causing the accidents. The person is relating to information, and relating to reality mediated by information, but the information bears no relation to the reality at hand.

A person’s opinion is formed on the basis of self-interest, wishful thinking, under the influence of their screen. But an opinion based on unreliable information has never led anyone to anything good. We have looked at how the screen is formed and what the consequences are. Why would anyone want to do this? The most important thing is the human factor. The whole hyperreality machine, the product of which is the screen, came into being in a context of social conflict and crisis, to control the human factor, to make all people a derelict herd, and frankly to make them fools. Hyperreality is an effective means to defuse the forces which otherwise undermine social control. The fact is that people with a sense of their status (whether as workers, farmers, businesspeople…) demand more from the state, they are difficult to control, but the masses are much easier. The category of the fool is vulnerable and helpless. It has no power component or cannot use its power component and all this has lasted for generations. This is advantageous because helpless people who know nothing and can’t do anything can’t change the social order. The prevailing mass of fools is a natural social safety net that ensures the established order will last.