The Old House on the Hill: an American Gothic Landmark of Social Displacement and Estrangement in The Addams Family and Psycho/Bates Motel

by Prof. Frédéric Conrod

Abstract:

Since its independence from Britain, US culture has established a clear connection to Gothic architecture thanks to its tendency to reconstitute Gothic landmarks on its land. Jean Baudrillard claims in America that: “One of the aspects of [the Americans’] good faith is this stubborn determination to reconstitute everything of a past and a history which were not their own and which they have largely destroyed or spirited away. Renaissance castles, fossilized elephants, Indians on reservations, sequoias as holograms, etc.”. Unlike European Gothic, American Neo-Gothic from the Gilded Age finds many of its expressions in isolation. This article seeks to explore from the theoretical perspectives of reconstitutions, displacement, and social estrangement how this phenomenon translates to the narrative continuum of the ‘old Neo-Gothic house on the hill’, a collective imaginary shared by and projected in The Addams Family and Hitchcock’s Psycho, as well as its recent prequel Bates Motel. This house is more than a Neo-Gothic building in decay; rather, it is the headquarters of an entire social minority. At the same time, it is the only territory in which such society can function.

__

When the wooden roof of the World Heritage Cathedral Notre-Dame of Paris burned accidentally in the spring of 2019, a deeply shocked American public, amongst other Western audiences, rushed to display on social media their personal and emotional attachment to this historical Gothic French landmark. Within hours, millions of dollars in donations had been wired to the French government for reconstruction of the Medieval roof. Why would a country, with no Gothic building ever constructed on its land during the Middle Ages, show such a tremendous dedication to the partial loss of the Parisian cathedral? In the United States, this strong sentimental connection to—and fascination for—what is essentially Medieval art and architecture embodied in the Gothic complexity started in the 19th century, once the Neo-Classical preference of the Founding Fathers started to fade out in the construction process of the American metropolis. The Gothic architectural challenges to Europe, such as the Cathedral of Learning and the Heinz Chapel on the University of Pittsburgh campus, became a common sign of extreme wealth, but this trend also affected the construction of private homes.

In order to fully grasp why America loves to reproduce Gothic architecture, we might find a starting explanation for this enthusiastic response to the European Gothic by Americans in the writings of Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard’s cultural theory focuses on the birth and particularities of US culture and its relation to the rest of the Western world; as Maria Beville underlines, “From a perspective influenced by the theories of Baudrillard, Gothic post-modernist works may be seen as manifestations of ‘the spirit of the terror’ and their metonymical structures, as the symbolic ‘event’ of terror which has the potential to destabilize hegemonic systems of order” (199). In his 1997 text America, Baudrillard wrote that “[one] of the aspects of [the Americans’] good faith is this stubborn determination to reconstitute everything of a past and a history which were not their own and which they have largely destroyed or spirited away. Renaissance castles, fossilized elephants, Indians on reservations, sequoias as holograms, etc.” (41). The impact of Gothic architecture during the High Middle Ages does not escape this rule in this fundamental feature of American culture. Perhaps the counterpart to the architectural breakthroughs that the United States has always sought to emphasize in its urban centers is precisely the reconstitution of the “old” accompanied by the voluntary decay of the buildings to echo the erosion of the Gothic in Europe; in other words, a Neo-Gothic structure that would look too neo would not look Gothic enough. Therefore, the decay and the erosion are often conceived along with the construction, or become part of the design itself.

Amongst other American reconstitutions, the United States is a country very keen on medieval architecture, reproducing it on numerous occasions. However, these structures lack truly Gothic authenticity, due to America’s Western history beginning with the religious migrations during the European Renaissance, a time period marked by its desire to replace Gothic features in architecture and art in general. Rather, Gothic architecture can only be a reminder of the pre-Reformation Catholic hegemony ruling over Western Europe, which is still deeply embedded in America’s cultural values and ideals in the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, the American fascination for Gothic buildings—particularly in contrast to the Hispanic Central and South Americas, that have fewer Gothic reconstitutions, preferring in general but not exclusively to embrace Baroque architecture, from Mexico to Argentina—continues into the present, with several waves of British and American architectures adapting the Neo-Gothic to another kind of construction: the “old house on the hill,” or an isolated, private estate symbolic of displacement and estrangement that voluntarily projects the Neo-Gothic aesthetics unto the passerby.

In addition to this fascination for a time period this country’s history has not experienced, it is often shocking for the continental European visitor to the United States to contemplate the level of isolation some Americans choose to live in. Baudrillard echoes this idea, noting that “It may be that the truth of America can only be seen by a European, since he alone will discover here the perfect simulacrum – that of the immanence and material transcription of all values” (27). Although it is not uncommon to find isolated buildings in Europe, they seldom seek to project architectural originality. Conversely, Americans have entertained the need to reconstitute, and therefore displace, Gothic projections in an effort to compile and reunite all the architecture from Europe in the wildest places of their virgin territory, as can be observed on the Las Vegas Strip, a concentration of exaggerated constructions in the middle of the desert. Indeed, the United States has always had a different approach toward architecture since its founding as a nation after declaring independence from Britain, a country with a heavy Gothic presence and heritage.

Offering myriads of self-sufficient properties built on a virgin land, far from urban centers and in direct contact with wildlife, the United States nonetheless still makes a conscious architectural statement about its European identity and ties, whether it is in the architecture of the Gothic, Baroque, Victorian or Tuscan styles. Such is a mark of conquest and colonial imposition that stands in isolation and solitude in order to provoke fascination. As Gaston Bachelard suggests in the Poetics of Space, “We are hypnotized by solitude, hypnotized by the gaze of the solitary house; and the tie that binds us to it is so strong that we begin to dream of nothing but a solitary house in the night” (36-37). In the case of “old houses on the hill” in the United States, the hypnosis serves two very different but meaningful functions: the first, as a means to make the beholder dream about a history that never was, and the second, to demonstrate the settlers’ desire to replicate and perpetuate a European historical thread, a physical reminder of the effects of the European colonizing presence during various points in their history. To state this more simply, the house simultaneously projects two pasts: one idealized, and the other of its actual colonialized past. These old houses, in spite of this paradox, bear a responsibility to project historical continuity, hence the need for a narrative continuum in American fiction.

Yet these ambitious projects, often a two-story mansion with a central winding staircase leading up from the foyer and a front façade tower, dark wood frames, and Neo-Gothic stained glasses are difficult to maintain for both technical and financial reasons. They were not built to withstand the test of time, but rather to project one’s wealth on a façade by way of Baudrillardian simulation. Consequently, their decline echoes the displacement of social classes as the country continues its progression through late-stage capitalism, as well as in the estrangement of minorities through this process. Not all historic houses have had the chance to be restored and updated with lasting materials, and many have fallen into disrepair. In Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel Psycho, the old house on the hill is perceived as such by Marion Crane, the first victim of Norman Bates:

At first glance she couldn’t quite believe what she saw; she hadn’t dreamed that such places still existed in this day and age. Usually, even when a house is old, there are some signs of alteration and improvement on the interior. But the parlor she peered at had never been “modernized”; the floral wallpaper, the dark, heavy, ornately scrolled mahogany woodwork, the turkey-red carpet, the high-backed, over-stuffed furniture and the paneled fireplace were straight out of the Gay Nineties. There wasn’t even a television set to intrude its incongruity in the scene, but she did notice an old wind-up gramophone on an end table. (32)

Contrary to what Baudrillard would suggest in his Consumer’s Society, this space does not want to reproduce the “networks of objects” of the early 1960s, which consists of “no longer relat[ing] to a particular object in its specific utility, but [rather] to a set of objects in its total signification” (27). We can arguably add that the unaltered setting Marion observes in the Bates’ parlor is a manifesto of anti-consumerism. The image of the decaying old house has served cultural needs to signify the deranged, the marginal and the socially estranged, or those who can bear living without updating or upgrading in the spirit of Capitalism, such as recluses and the freaks who refuse an economy of constant consumption, desires, traditions and feasts often observed in a bourgeois culture. Thus, the decaying building inhabited by the socially marginalized has a second life that is much more fascinating in the cultural, literary and cinematographic expressions of the United States.

Of all these landmarks marking a fallen age of prosperity, the properties from the American Gothic, or more accurately the Neo-Gothic Gilded Age of the Gay 1890s, are the most representative of hegemonic power, positioning these structures—and the people who owned them—against those suffering from psychosocial deviations and dysfunctional families living on the outskirts. This recalls similar hegemonic structures of Gothic Paris, insofar as these buildings and their implied socioeconomic status was in direct opposition to the Cour des miracles, a community of beggars, thieves, heretics and prostitutes in Gothic Paris living extra muros, or outside of the city’s walls. Yet the Neo-Gothic style that emerged in the United States at the turn of the twentieth-century proved paradoxical for Gilded Age millionaires, as even those who were building enormous fortunes would not always leave sufficient funds behind them. With heirs often incapable of maintaining a house made of fine and somewhat ephemeral materials, the majority of these houses were left to perish or be passed along to lower-class inhabitants who would find satisfaction in owning a symbol of status, even as an outdated structure they had no capacity to renovate. Yet some families fought their best to keep the symbolic house built by their ancestors, in spite of the financial hardship, just in case another Gilded Age would arrive for them to have the capacity for restoration. Without a second Gilded Age, however, these houses fell only further into disrepair, allowing for the American imagination to flourish. The result—an American fascination for ghosts inhabiting these spaces of past glory—permitting for property values to be maintained or even increased. In the meantime, the American fascination for ghosts inhabiting these spaces of past glory has often maintained a certain level of value for the property at stake. Similarly, “ghost tours” have proven to be very lucrative touristic attractions in certain historic homes or neighborhoods, not only for the dwellers, but also for any by-passer; in effect, the decayed mansion is a landmark of social periphery. Some Americans deliberately choose to live there, while others can contemplate these isolated buildings as a visual representation of marginalization both past and present.

Further, the geographical location of the estranged “old house on the hill” is often, and by definition, purposefully odd. Whether the urban zone has never reached the land on which it is built, or whether the Neo-Gothic mansion was voluntarily built on a land where the city could never possibly arrive, its position is never easy to locate on a map, and it draws its haunting character from its difficult access, usually reinforced by high gates, hilly terrain and/or staircases. In a rarely urban context, it will be found in a dead end, perhaps through a dark alley, and always with a mysterious horizon as its minimalist background. The qualities afforded from its downward-spiral, mystic vertical façade—in both a physical and metaphorical way—rises from the feeling of an unreachable/forbidden territory it projects from the outside, and somehow obligates the viewer to venerate with emotions similar to the ones provoked by Gothic churches. According to Misty Jameson, “[t]he gothic has often been employed by writers desiring to expose the excesses of religion, particularly the utopic impulse that can, in radical forms, lead to a desire for destruction” (316). Displaced from its historical context, the old Neo-Gothic house on the hill therefore becomes for popular culture a three-dimensional symbol of the dystopic Freudian Death Drive embedded in the social tissue.[1] According to Baudrillard,

the alienated human being is not merely a being diminished and impoverished but left intact in its essence: it is a being turned inside out, changed into something evil, into its own enemy, set against itself. This is the process Freud describes in repression: the repressed returning through the agency of repression itself. (190)

This mansion thus becomes the space where society begins its dysfunction, providing a path to delirium and madness, while also serving as a refuge from the frantic consumerism that has invaded the rest of the nation. It only takes one small group of dissidents to make such statement.

The implications of the American fascination with the “old house on the hill” are only further reinforced through fictional productions, such as The Addams Family or the several representations of the Bates Motel, both fascinating examples of the American Neo-Gothic narratives. What would the Addams Family, whose decaying old mansion is the most visible statement of their mission to be an anthesis of the system, represent to an American society that relies so heavily on cookie-cutter consumerism? Likewise, what theatrical value would the Bates Motel have if it weren’t an addition to the older home up on the hill behind it, on the outskirts of prototypical small-town America? Although these two buildings both pertain to unrelated fictions from different genres, the Neo-Gothic signifies the same social estrangement for these two fictions: the decaying old house becomes the living space of the freaks. Without a doubt, the Addams are freaks by choice, tradition, and free will to reject the hegemonic models; the Bates are questionable when it comes to evaluating their degree of free will in inhabiting the space, but they benefit from psychological consequences of traumatic circumstances. Thus, the Gilded Age mansion becomes through its visible decadence the space of that alternative microcosmic society that doesn’t follow the rules of social order and consumerism and, by and large, those of a Capitalist structure. Ironically enough, their very construction was indeed motivated by Capitalist ostentation, but their uchronic characteristics progressively turn them into landmarks of dissidence against the economic system in place in the United States since its foundation as a nation. By the second half of the twentieth century, the old house on the hill appears in the collective unconscious as the unseemly evidence of social failures: where there used to be an apparent accumulation of wealth, we now find what Baudrillard equates to the ghost towns, that is, the ghost people. The inherited decaying mansion, the ghost house, has to be haunted or inhabited by freaks: their presence hides any evidence of, and participation in, the simulations of a consumer society.

The Addams Family and the Psycho/Bates Motel American archetypes of marginal citizens inhabiting the “old house on the hill” have a rather complex relationship to capitalist consumerism. While the Addams are somewhat living a systematic and antithetic workless lifestyle, they can survive thanks to an underground bottomless treasure whose origin is never explained, but dates back to the Middle Ages and was also displaced. As the original 1964 television show opening credit soundtrack claims, “their house is a museum where people come to see’em”, and they do collect remains of a historical past, often more Medieval and projecting tastes for an era when the Inquisition reigned over European Catholicism. Heirs to non-Christian antagonist figures for U.S. Puritan society and subsequent rejects of society in U.S. History, the apparent frugality symbolized by the same clothes the Addams’ always wear rests on another kind of capitalist behavior: the collection of historical objects and furniture that were never American but completely European. But this infinity of unexplained wealth is what protects them from popularity and social obligations; despite being alienated by society, they can continue to live their dream of symmetric opposition to the consumer society. When Charles Addams creates this atypical death-driven family in the 1930s, in an era when Freud’s ideas influence artists of all kinds and nationalities and the West is about to enter a time of unprecedented carnage engineered by collective Death Drives, the Gilded Age has already shown signs of irreversible decay. Yet Americans were entering in a post-WWII fever of procreation and suburban materialism that would last until the present day. What could be funnier than the home of Gomez and Morticia for a young couple recently in debt and equipped with the latest generation of electronics? A fantasy, an escape, a negative picture? What could be more reassuring than their offspring, Pugsley and Wednesday, for a baby-boom culture that would place children at the marketing center of all family life and home economics? The 1950s and the 1960s, in particular, strived for those symmetrically opposed marginal figures in order to understand their mechanical reproduction.

The Neo-Gothic Gilded Age imagery in decay was also a reassuring reflection, since in the aftermath of WWII, Americans were led to believe that the suburban consumerist middle-class model was the greatest economic system that had ever been established in world history. By implicitly guaranteeing that every member of American society could have access to this model if they were willing to submit to interest rates and accept debt as the norm, while never revealing that the space they would inhabit could ever be truly owned, the rhetoric proved to be effective to the masses. Indeed, consumerist middle-class Americana would keep them safe from both the raging nineteenth-century Capitalism of the great family dynasties who took charge of the economy during the industrial revolution, such as Carnegies, the Mellons, the Morgans or the Rockefellers. These self-made empires sought to revive the feudal imagination through their taste for the Neo-Gothic in the construction of skyscrapers as well as country mansions, even though they had seen a great majority of their grandparents entrapped in the working class during their entire existence.

Later on and well into the twentieth-century, in the context of the growing threat of erasing social difference that Communism represented, Charles Addams creates his own displaced and estranged family dynasty at the beginning of the Cold War, and soon after The Addams’ Family premieres in a decade marked by the tensions between Capitalist societies and the Communist bloc. Along with The Addams Family, other 1960s sitcoms such as Bewitched and The Munsters, emphasized through a negative reflection the preferences for a consumerist lifestyle via a very simple mechanism: create scenarios which present anything deviating from the “normal” as being foolish, laugh at the freaks, and do well in believing in the consumerist mentality.

“Sic Gorgiamus Allos Subjectatos Nunc,” the historic family motto emphasized by Morticia Addams to her brother-in-law Fester in Barry Sonnenfeld’s 1991 feature-film about the estranged family, reflects this opposition to the Consumerist model promoted worldwide by US society since World War II. It also echoes an awareness of the Hegelian Master/Slave dialectic and a common will to reverse its dynamics, as the subdued become the masters of their own game living in the autarky of the old house. The phrase’s somewhat Medieval/Gothic translation into English, “we gladly feast on those who would subdue us,” points to a political message on the part of a family who has shown resistance to the imposed models since the very colonization of the future United States by the Founding Fathers. They are projecting that they have lived on the land according to their own rules, not those of the American Constitution, Republic and Democracy. Yet this motto is also a “reconstituted” Latin, once again echoing the “stubborn determination” defined by Baudrillard to pretend a historical past that never existed. The fake Latin of the Addams reflects the illusory nature of their demarcation from the rest of society, as well as their partial failure to live in total autarky and anti-consumerism.

Their reconstituted historical landmarks, associated with the Addams family’s mission to resist the norms since the seventeenth-century, are next to the old house on the hill in their family’s private cemetery, and stand as a constant reminder of their post-existentialist philosophy of marginal American freaks. The house is more than a Neo-Gothic building in decay; rather, it is the headquarters of an entire social minority. At the same time, it is the only territory in which such society can function, and the Addamses can only have extremely limited interaction with the outside world in their voluntary estrangement. For the outside viewer, this territorial restriction means more than isolation, as it also signifies potential island fever or even claustrophobia. Speaking more to this idea, Jameson adds that “Gothic claustrophobia is now part of postmodern paranoia, the fear of enclosure within some type of vast, impersonal system” (318). Nonetheless, this necessary claustrophobia is the sine qua non condition for estrangement to signify resistance in the visual standing of the old house on the hill.

But this still does not resolve why the Neo-Gothic, an aesthetic movement driven from the late Medieval trend of the Gothic itself, is such an archetypal force on the American collective imaginary. “Neos” are usually indicators of complexes, such as can be witnessed by the Neo-Classical macro-visions of Napoleon Bonaparte, the Corsican soldier who turned himself into a reincarnation of Emperor Julius Caesar and therefore promoted Neo-Classicism. Yet Saint Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City was not built between the fourteenth and fifteenth-centuries, and Neo-Gothic buildings also have this capacity to denounce this complex or envy of a nation who wants to cope with a deficiency. Making the Neo-Gothic space a limited territory for the resistant freaks, and provoking claustrophobia in the observing public, are two potential resolutions to the obvious complex in question. In the progression toward postmodernity, the American Gothic—in itself a contradiction—has turned to signify rebellion and rejection of the hegemonic norms.

Amongst the Halloween symbols that invoke the Gothic, the “old house on the hill” is a leitmotiv, and people will often opt for a reconstitution of this ambiance for the American version of the feast of All-Saints. On October 31st, a considerable portion of American consumerists seek to become a freak: a Frankenstein monster, an Addams or a Bates, or whomever else can reconstitute Gothic imagery. Yet this atmosphere, so familiar to the Addams or the Bates during the remaining 364 days of the year, is a one-night only affair for all others. Calling on Mikhail Bakhtin’s conclusions on re-establishment of social order through carnivalesque reversals in Rabelais and His World, the freaks are revered as the royal figure for a brief moment that reaffirms social hierarchy. Power is stabilized through such projected inversions. Without any ostentatious evidence of religious beliefs in the space, occasional visitors are struck by the ongoing carnivalesque nature of the space. Entering the old house on the hill is not only a challenge to the established norm, it requires a total acceptance of its inversion. Social hierarchy is voluntarily perceived upside-down, as it is normally accepted during carnivalesque events such as Halloween. The Gothic imagery also serves as an ekphrasis on the High-Middle-Ages collective imagery of the crowning of the fool; that is, bringing the lowest element of society to the top of the power ladder, just for ephemeral aesthetic pleasure, and eventually reaffirmation of the current order.

In the old house on the hill, the space is not only carnivalesque in its quotidian existence, it is also anti-chronological. The landmarks of the passing time are purposefully arranged in reverse. Everything becomes a negative print of the present normal consumerist society. The Gilded Age mansion is filled with objects from different time periods placed in odd juxtapositions of random collectibles, which only make sense within the reactionary educative syntax of the family. Whether it is the Addams or the Bates, it is based on a rejection of the present, the future and the technological revolution. Also, both houses project a similar taste for taxidermy, another reverse-the-course-of-time hobby that Norman Bates practices in the basement as therapy for his rather chronological tendency to turn live women into cadavers. The Addams children are raised in the midst of this ordered chaos. The house is a sanctuary in which they can be raised against the grain, play with torture instruments or practicing taxidermy instead of exercising or playing with a live animal. These stuffed corpses whose expressions are threatening serve as indoor gargoyles for the Addams family as well as for the Bates mother-son tandem and, by and large, fulfill the same purpose of frightening the occasional visitors as they would on the walls of Gothic cathedrals, with the exception that they do not point to the existence of the Inferno in the afterlife, but rather to the acceptance of infernal conditions in the present reality of America.

Ultimately, this sanctuary is also a sacred place for an alternative education, even though the children all go to public schools and have daily interactions with hegemonic norms. Wednesday, Pugsley, and Norman are raised in the Neo-Gothic spaces their parents have conserved and cured for them as safe haven from consumerist and technological invasion from the outer world. No television is ever to be seen in the Addams mansion, ever. The addition of this invasive commodity in the Bates’ 1920s living room, when the mother Norma starts to date Sherriff Romero, an alpha male who brings a brand-new big flat screen in the living room once he moves in the old house, triggers Norman’s rage against his new stepfather. The only noise allowed in the old room are the piano and the gramophone when mother and son live together. The musical instrument of the organ is also very central to the Addams’s daily routine. While the Addams are stuck in a self-invented historical past, the Bates have chosen to start afresh in a house filled with furniture from the first half of the twentieth century, connecting the Victorian era to the pre-WWII. The Addams’s and the Bates’s old mansions stand, in this sense, as bastions against the baby boom of the 1940s and 1950s. They refuse to participate in the demographic growth as well as the consumerist attitudes. The apparent extravagance of the old house is a façade for an extremely frugal lifestyle in both cases. Nothing is wasted, and most components are recycled or restored; very rarely is money spent to “update” anything in the interior space.

Ultimately, the old house on the hill is a deeply feminine and maternal space. Even though it has a clearly phallic façade with its common central tower, the central element that holds the Neo-Gothic building together and gives it its ideological coherence is the central staircase, and this keystone element of the house is clearly the practiced space of the mother in the family, whether it is Morticia or Norma. Both extremely attractive, sensual, and sexual women characters in these fictions, they project a sense of the abnormal from the point of view of the consumerist sexual guidelines for women. Far from the standards of beauty imposed by the surrounding consumerist present, these two female figures cultivate a style of their own, pointing to an atemporal historical past that never was. They embody and offer a definition to what an American Neo-Gothic woman would be, to a certain extent: Morticia for her appearance and family values, Norma for her determination to raise Norman in the margin of the present cultural modalities of corrupted exterior space. The whole prequel of Hitchcock’s Psycho, the A&E series Bates Motel, is precisely based on focusing on the character of “Mother,” Norma Bates, left unexplored in both the 1960 movie and the novel by Robert Bloch who inspired the British director. Vera Farmiga, the series’ executive producer and producer as well as its lead actress, emphasizes in most interviews she has given about Bates Motel[2] that from the perspective of this three-layered position she occupies in the show, the importance of placing the mother figure is at the very core of the old house. While Norma’s project to isolate her son from the potential dangers of the outer world seems completely unreasonable at first, and presents itself as the very origin of Norman’s pathology, the viewer progressively sympathizes with this anti-consumerist attitude and the need to return to a safe haven such as the old house behind the motel. The disparity of architectural styles between the old house and the motel reflects the same disparity between the generational conflicts at the roots of Norman’s psychosis with women, based on his incapacity to leave the house representing earlier generations, and by and large the building that represents his mother’s womb. Norman’s most emblematic and first victim across narrative iterations, Marion Crane (interpreted by Janet Leigh in 1960, Anne Heche in 1998, and Rihanna in 2017) feels a strong attraction to the old house on the hill as she admires it from Norman’s office down at the motel, seemingly perceiving its female nature beyond its phallic façade. As Diane Negra proposes regarding Norman’s connection to the maternal space, “the male protagonist’s connection to feminine values is intended to serve as the narrative explanation for his murderous impulses” (195). In the prequel Bates Motel, his decision to commit suicide in the house with his mother—and using the house as the very instrument for their shared deaths—is his only solution to return to a pre-natal state, in the womb of his mother. Consequently, I would argue that the house is, across the whole narrative continuum of Psycho to Bates Motel, the very catalyst of Norman’s connection to his tragic murderous impulses: it is simultaneously what causes, reactivates, and appeases his mental condition and its pathological outcomes.

The comic Addams Family paradigm, with a Halloween 2019 release of an animated version returning to the original drawings of their creator Charles Addams, also emphasizes the matriarchal nature of the old house on the hill. Obviously not digging as profoundly in the psychology of its characters as Psycho/Bates Motel, it offers a systematically negative reflection of American society, insofar as viewers are supposed to contemplate the relativity of their own values and find inspiration for proper social conducts in its antithesis, a common feature in many TV series since World War II. As discussed previously, the Addams’s withdrawal from the world is partial since they maintain minimal contact with the external world; however, their isolation begins once they have all returned from their daily occupation. Yet they function as the counter-example to what American culture needs in the construction of language systems, symbols and laws, or what would correspond to its Super Ego (Freud), its order of culture (Lévi-Strauss) or its Symbolic Order (Lacan) in the theoretical approaches from anthropology and psychoanalysis. And although Hitchcock was not a director of comedies, he certainly appreciated and shared a lot of the projected negative values his friend Charles Addams had drawn. They both understood what the post-WWII re-visitation of Freudian psychoanalysis implicated for the world of fiction and the role that a socially estranged family could play from the periphery of an old house.

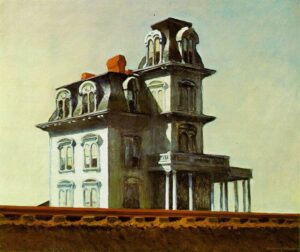

The British filmmaker Hitchcock and New-Jersey-native Addams were not only intimate friends, but also drew a common fascination for the old Gothic mansion on the hill. Charles and Alfred might have taken two different paths and came from two distinct continents and cultures, yet there was something comic in the tragedies of Hitchcock just as much as there was a high level of tragedy at the very center of Addams’s comic drawings; in fact, two of those drawings were owned by Hitchcock (Davis 27). Also at the center of their shared imaginary and mutual admiration around the old Neo-Gothic house was a photograph by Edward Hopper titled House by the Railroad from 1925 (Figure 1). What is striking and common to all three copies of the old house (Hopper’s, Addams’s and Hitchcock’s) is their common lack of background. Trees, stairs, or gates always appear in the foreground, emphasizing the distance between the viewpoint from below and the house up on the hill. However, nothing but an occasional moon or other celestial object ever appears in the back, always suggesting an emptiness, a void, and ultimately a frontier or borderline of existence. This big empty lit sky in Hooper’s original photography, as well as in its many derived paintings, is precisely what fascinates every viewer.

Figure 1. House by the Railroad. Edward Hopper, 1925

(Public Domain)

The caption of the edited volume quoted in Figure 1 points out that the House by the Railroad photography projects “melancholy and lonel[iness] rather than menac[e] and evil”, but this is very questionable since the house, in both comic and tragic expressions alike, is precisely the very locus where all these emotions come together and become indistinguishable. Robert Bloch definitely perceived this function of the old house when he imagined it for the formation of his character Norman Bates. A pioneer of tragi-comic science-fiction, Bloch found inspiration for his masterpiece Psycho in the fait divers dealing with dissociative identity disorder of serial killer Ed Gein. However, this local news from Plainsfield, Wisconsin did not involve an old Neo-Gothic Gilded mansion standing alone on a hill, but rather an isolated farm ruled by a Christian fundamentalist mother. Bloch himself insists on the originality of his character and his unusual space of residence:

Thus the real-life murderer was not the role model for my character Norman Bates. Ed Gein didn’t own or operate a motel. Ed Gein didn’t kill anyone in the shower. Ed Gein wasn’t into taxidermy. Ed Gein didn’t stuff his mother, keep her body in the house, dress in a drag outfit, or adopt an alternative personality. These were the functions and characteristics of Norman Bates, and Norman Bates didn’t exist until I made him up. Out of my own imagination, I add, which is probably the reason so few offer to take showers with me. (19)

According to this same disclaimer logic, the old house on the hill did not exist until Charles Addams, Robert Bloch, Alfred Hitchcock, and others who followed the narrative continuum of their respective stories (Gus Van Sant for his sequels of Psycho, Vera Farmiga for the prequel Bates Motel, Barry Sonnenfeld for the 1991 version of The Addams Family, all the way to Conrad Vernon and Greg Tiernan with the 2019 animated remake of the Addams Family) made it up. The connection between the Gothic imaginary and the merging of comedy and tragedy is, of course, hardly a recent phenomenon, having had anterior expressions in fictional works, most notably in the Romantic period. Over the course of the twentieth century, however, it reaches a new dimension in the locus of the old house on the hill, becoming a universal cliché as well as part of a global collective unconscious. After the experience of two world wars, American culture has a need for more spaces of tragicomedy such as the old house on the hill: melancholic, isolated, frightening, and wicked. The two narrative continua identified here are indeed part of a greater continuum, as their creation paralleled the development of new theoretical approaches around intertextuality in the second half of the twentieth-century.[3] We could easily imagine a contemporary scenario where Norman retreats in the basement to work on his stuffed animals while Wednesday and Pugsley are chasing each other with his knives around the motel; where Norma and Morticia rearrange the collection of Victorian objects around the living room; and Gomez is locked in his office writing and posting fake news all over the internet. And this scenario depends on the old house, outside of which all of these characters completely lose their essence and purpose.

Four years after the publication of America, Jean Baudrillard returns to the debate with The Transparency of Evil, in which he opens with the claim that “[w]e live amid the interminable reproduction of ideals, phantasies, images and dreams which are now behind us, yet we must continue to reproduce in a sort of inescapable indifference” (4). In this sense, I want to argue in conclusion that the social displacement of the Addams and the Bates families in their popular fictional expressions, from the 1930s to the present, reflects the cultural estrangement of an entire nation reproducing Gothic phantasies and imagery. As an American reconstitution of a historical past that never was, the collective unconscious is invited to familiarize itself with a sample of freaks who have chosen to isolate themselves in an alternative lifestyle on the margin of the known world antithetic to the majority, and in a structure in decay, or not built to last long to say the least. We will never know what is beyond the old house on the hill because its depictions never allow it; we only know they have chosen to live on this geographical and psychological edge. Isolationism is an essential component of the American culture, with its roots and finds in the old Neo-Gothic house on the hill as one of its most poetic metaphors—indeed, it is a metaphor that will always depend on the quick recovery and reconstruction of the Gothic landmarks back in Europe.

References

Bachelard, Gaston. Poetics of Space. Beacon Press, 1998.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Indiana UP, 2009.

Baudrillard, Jean. America. Translated by Geoff Dyer, Verso, 2010.

—. The Consumer’s Society. Sage Publications, 2006.

—. The Transparency of Evil. Verso, 1990.

Bellville, Maria. Gothic Postmodernism: Voicing the Terrors of Postmodernity. Postmodern Studies, 2009.

Bloch, Robert. “Building the Bates Motel.” Mystery Scene, vol. 40, no. 19, 1993, pp. 19-58.

—. Psycho. The Overlook Press, 1959.

Davis, Linda H. Charles Addams: A Cartoonist’s Life. Random House, 2006.

Jameson, Misty. “The Haunted House of American Fiction: William Gaddis’s Carpenter’s Gothic.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 41, no. 3, 2009, pp. 314-329.

Negra, Diane. “Coveting the Feminine: Victor Frankenstein, Norman Bates, and Buffalo Bill.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 24, no. 2, 1996, pp. 193-200.

Topliss, Iain. The Comic Worlds of Peter Arno, William Steig, Charles Addams, and Paul Steinberg. Johns Hopkins UP, 2005.

Endnotes

[1] The Freudian interpretation of the Death Drive (Todestrieb) initially introduced in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) is linked to the religious allegories in Freud’s later work Civilization and its Discontents (1930).

[2] Particularly in the following interview to Carina Chocano from The Cut: https://www.thecut.com/2017/04/interview-vera-farmiga-and-kerry-ehrin-of-bates-motel.html

[3] Especially in the proposals of French structuralist and poststructuralist thinkers, such as Roland Barthes and Jacques Derrida.