by Oleg Maltsev, Lucien Oulahbib

Chapter 1. Introduction. Why write this book?

“Greatness is not about a person himself, but his deeds”

Dr. Oleg Maltsev

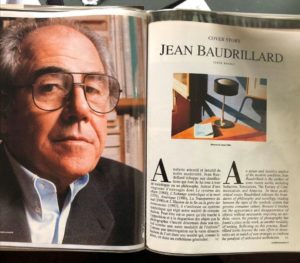

Jean Baudrillard. The last and the most eminent mastermind of the twentieth century. People like him are born once in a hundred years, and today perhaps, such novelty is witnessed even more rarely. For this reason, I have decided to write this book. In scrutinizing what makes this individual “great”, I am tempted to say he is not just “great” in the postmodern era of the last century, but he was also ahead of his time. He can therefore be seen as the last “prophet” of Europe. The contemporary interest in the works of Baudrillard during his lifetime was manifested in different ways, from crooked smiles to careful attention and fascination. Sometimes he was taken as a jester, playing with his readers’ assumptions with dystopian parodies of modern life. His works are no less eagerly sought after his death, and maybe even more so. However, people began paying very careful attention when things he had written about became our reality; it wasn’t funny anymore.

Why is Jean Baudrillard great? He has been the most popular postmodern philosopher in the world for more than 20 years. He was a source of misery and a bogeyman for many in Europe in the 60s, 70s, and even 80s. There was not a single major publication that would not consider it to be relevant to interview Baudrillard, and almost every major news publication has an interview or a piece about Baudrillard: the New York Times, The Guardian, New Yorker, Der Speigel, Die Zeit, Suddeutschezeitung, Liberation and Le Monde among many others. Many of the various interviews by journalists and scholars were collected into books titled Jean Baudrillard. The Disappearance of Culture[1] and Jean Baudrillard From Hyperreality to Disappearance.[2]

However, this popularity or notoriety was not always an expression of appreciation. Many found Baudrillard’s views perplexing. The theorist known as the “godfather of postmodernism” was even a “foreign substance” for America at the beginning. Yet his work was sufficiently unusual and unfamiliar to provoke exceptional curiosity. After all, Jean Baudrillard dared to criticize the US, calling it a “primitive society” in his book America. This may be typical enough of French perceptions, but from the perspective of those who are “100% Americans” it is an indescribable arrogance. Indeed, American colonial society is founded on its difference from the “primitive”.

Yet notoriety may indicate something different: Jean Baudrillard accomplished the impossible. He was able to become globally relevant as a public intellectual, to make waves in ways which few scholars ever do. He was capable of stirring society with his ideas, philosophy, anthropology, sociology, semiology, and even the style of language he used. And the fact that Baudrillard’s ideas, even in his lifetime, had supporters and opponents in the society of consumption which he identified as the central sphere of modern society, should be recognized as an achievement – even a civic feat.

Many people consider Baudrillard to be a Marxist, hence labeling him as an enemy of capitalism, but that is not completely right. He begins from the Marxist theory of alienation and something akin to a situationist theory of the spectacle, but later becomes critical of Marxism for keeping its horizons within the world of “production”. He thus concludes that Marxist proposals for change were insufficiently radical to alter the fundamental sources of alienation in modern life. His critiques always applied to administered “command societies” as much as to western market economies, and he increasingly saw both as subsumed in a type of cybernetic simulation which destroys the meaning of production itself.

Baudrillard reads and uses the works of Marx, along with those of Nietzsche, Kant, Foucault, Freud, and others. Yet he is original in their uses and is unafraid to reject those aspects of the theorists that he does not find useful. Similarly, he was influenced by Jacques Lacan, but did not become a full adherent of Lacan. In some of his works, if one reads between the lines, his main concern is to address the problem of “the people” themselves (not their oppression by some other system from outside). Yet he does not have in mind the standard Lacanian cure, if such a thing exists; he develops his own psychology through the notion of symbolic exchange, which is absent from Marxian, Freudian and Lacanian thought.

Many have an impression that Jean Baudrillard was critical of capitalism, and that’s not quite true either. He criticized people, and humanity; Baudrillard took on the heavy burden of formulating a critique of humanity, and not only capitalism. For Baudrillard, сapitalism is simply a relationship type in society; since it exists it was certainly scrutinized. Yet it is not made into the conceptual cause of all the problems of modern life. Baudrillard thus insists that capitalism has not solved the problems of humanity, that it is rather an effect of these problems. Indeed, Baudrillard also criticized the people, the social, the masses, and left-wing politics. His basic view could be put into one sentence: it is people who are responsible and guilty for all, if people were different and not a silent “mass”, everything else would be different. He does not argue that the people are innocent or virtuous, and are oppressed by an alien system which is outside of them. He argues that the agency of humans is itself entangled in their alienation.

And that is very reasonable. More than ever, people act as passive masses, following the hivemind generated from whichever algorithmic cluster they belong to. Today, many people do not understand fairly simple things due to a lack of education, and the further evidence of the “disappearance of culture” as was mentioned by Baudrillard in numerous interviews and texts. This leads to new forms of fatalism: uncritical faith in “experts”, “necessity”, the shibboleths of left or right and so on. Without a scientific approach to reality, people end up taking a religious stance, with various abstractions in the place of God. If we look at widespread “religious” approach, when people say “It’s all in god’s hands”, “God has created the world and therefore he knows what to do,” and people are just “an aftereffect of a certain god”, therefore everything that happens in the world pleases God. However, empirical observation demonstrates that people are ones who shape the world and not God. Today’s consumption, media and political clusters often function in a similar manner, with the role of God taken by one or another sign which unifies the group, while eluding human agency.

Provided this question is looked at from a philosophical perspective, certainly, it is possible that somebody created human beings, and theoretically, possibly it was God. But once he had done it, he would no longer interfere. All the rest is done by people, supposedly helping God to build this world. If we remove the “divine concept” as such and exclude God for a moment as we cannot disprove or prove its existence, then, of course, it would be correct to say that this world is built and shaped by people themselves. Hence, there is an interesting conclusion: all problems come from people (except natural causes (hurricanes, earthquakes, etc.) that are not in the hands of people). For this reason, Baudrillard criticized humanity and not capitalism. If you consider the entire volume of his works, roughly speaking he devoted a third of his life to “exposing” humanity. There is a whole spectrum of descriptions: masses, society of consumption, silent majority, screened out, the kingdom of the blind, carnival of mirrors, participants of the orgy… one may see for themself how much attention the problem of the people receives. Baudrillard “mocks” humanity for 44 years (1970-2014). In fact, that is an act of courage, as humans can easily get offended at such criticism and treat Baudrillard as a bully.

At least a third of Baudrillard’s philosophy is a critique of humanity. The main notion for the great philosopher in this regard boils down to the following: this world is the way it is because of the way people are! As simple as that. If the problem is that the media is intolerable, Baudrillard’s position maintained that if you stop accepting what the media feeds you, then they will have no choice but to adjust. As the media changes, it will force politicians to change too. After all, it is very simple: stop watching and following the media, then they will have to change. In fact, mass media organizations will become unnecessary in the way they exist now. They are in high demand only when they can influence the masses, society, the electorate… but if they have no influence over people, they become useless and will have to change accordingly. Imagine a show presented in a circus or theatre without an audience. Nobody came to watch the show, nobody paid money for it; so why would artists work in an empty hall? Same thing with the media. Any Spectacular, alienating, propaganda, or subjectifying effects are not going to work if nobody reads newspapers or watches TV shows. That is why Baudrillard argued that the problem is in people themselves. If we conventionally divide Baudrillard’s works into three parts, then the person would be in the center of it all, not the mass, not the screened-out, not the electorate but the individual.

Equally important is the fact that Jean Baudrillard is not only the last and one of the most famous philosophers in the world, but also one of the last mystics of this world. He was a mystic without a doubt (though not a “guru”), and this will be discussed later.

It is impossible not to mention that the “godfather of postmodernism” was a very well-mannered and modest man. Otherwise, it is likely that he would have written a book titled Incredible Fool. How else can one term a rather strange, modern and average substance? But Baudrillard did not author a work that would imply the aforementioned title. When I began studying Baudrillard’s writings, I realized that this is a philosophy that analyses the psychology of inferiority and the dependence of modern humans on authority. Сonsidering today’s “strange” individuals from this angle of psychology, it could be said that they are inferior, they feel themselves to be inferior and they even aim to be inferior. Baudrillard’s theoretical texts are an excellent ground for studying this subject of depth psychology as the psychology of inferiority. This is my own term and not Baudrillard’s, but I believe it is a continuation of his work.

Jean Baudrillard thus takes a position like that of a tragic hero. He is great, not because some consider him as such but because he was capable of opposing himself to all mankind. Though not only opposing but also winning the battle and gaining immeasurable popularity and introducing his ideas to millions. He is quoted indefinitely. He is intellectually challenging for many and this list may go on and on. One man. All by himself.

Baudrillard has also accomplished another more vivid feat: opposition to the whole of European academia. This was the second object of his studies. Thus, if the first object of study for the philosopher and sociologist was the “masses”, “screened out” and narrowed down to a single individual (the “fairy-tale fool”), the second block of Baudrillard’s quest was the juxtaposition of his own discourse against the entirety of European academia. And he argued in his works that academic science (in which I am including not only the natural sciences or quantitative research, but all research scholarship, “science” in the German or Russian sense) is not exactly academic, because it is false. It’s a hoax, a simulation. The facts it produces are circular: it feeds the masses signifiers which it then re-extracts from them. It does not produce knowledge of the world or ways of acting in the world; it provides simulations which are used as blueprints to generate or simulate a world, which nevertheless remains several degrees removed from anything which seems “real”. It is clear that this paradox exposed by Baudrillard persists today.

Modern science, at least in its postmodern form, is no match for ancient science. Ancient science is a science of life, closely connected to crafts and technologies, techniques of living and ways of directing human agency to transform or relate to the world. Modern science did not appear from scratch, and at the same time, it is rather strange: it has never existed in nature. It is not an outgrowth of practices of living, but rather, emerges as part of the simulation of a social world. From Baudrillard’s viewpoint, modern science “appeared” in parallel with the Bourgeois Revolution; it provides the very science that was needed to serve consumer society (and which is very different from the earlier, fundamental science). A science that serves consumer society is bizarre and has little to do with real science, and it causes a number of paradoxes.

These paradoxes are quite simple ones. The first of these is the paradox of fragmented vision. Each of the sciences is a separate entity with its own methods, theories and assumptions, yet the same practical issue or activity is often the subject of multiple sciences, requiring “interdisciplinary” knowledge. An issue like economics, considered only mathematically (or only ecologically, or only sociologically, or only physically…) is not considered objectively and factually; too much is left out. The choice of scientific discipline and of method “biases” determines the conclusions. The objectivity of science is fractured to such a degree as to become inaccessible. It sometimes becomes possible to consider a certain subject objectively only in the case that it is examined from the perspective of 160 sciences simultaneously. Simple question: who is going to read so many works? Just like back in the day medicine was divided into “parts”, science at some point branched into different components. Today it has fallen into a state where only scientific work carried out at the intersection of multiple sciences (not a single specialization) comes close to the truth (i.e. corresponds to three components of the truth: verifiability, multi applicability, and effectiveness); an approach which is not accepted by most parts of American academia, for some reason. European colleagues encourage multidisciplinary research, but this is often frustrated by an attempt to combine multiple incommensurable approaches; sometimes the specificity of a method is lost. In other parts of the world, figuratively speaking, “a historian should only be a historian”, “a philosopher could only be a philosopher” etc. A scientist should not be both (philosopher and historian) at the same time, which sounds rather absurd, but on the other hand, each branch of science has preserved some features of the exact sciences.

About the methodology of science.

Real science is about discovering and understanding zones of the unknown, expanding both knowledge and agency. This goal requires that science be both oriented towards concrete social and practical questions, and that it be autonomous from requirements to conform to political or corporate interests. Today the conditions for such a science do not exist. This is paradoxical, because science is not directly censored or controlled, and scientific methods and tools have developed to an exceptional degree. In today’s world, scientists have all the tools permitting them to carry out unbiased, reliable and objective work. Today’s home computers have more processing power than the entirety of the Apollo mission control; the discoveries of centuries are available at the click of a mouse. But strangely enough, the average scientist has become extremely conservative about investigating the unknown or understanding and criticising methodologies. Scientists prefer to continue well-trodden paths and re-using methodologies, the rationale for which they do not understand, or rehash similar ideas without original discovery. In real science, methodology is an interactive, pragmatic and experimental field. Scientists need to consider existing methods or even develop new ones as they encounter problems in the field of knowledge, as ways to uncover the unknown. Today, what instead happens is that scientific methods are employed like algorithms: scientists study one or two established methods which they “choose” at the start of their study and apply mechanically to the subject-matter. The result is a weak kind of research in which the chosen method stilts the outcomes, and research results arising from different methods are unable to speak to each other. This is quite easy to confirm; just pay attention to the fact that year by year there are fewer and fewer scientific discoveries compared to the achievements of scientists and the number of discoveries in (say) the 1930s. These discoveries were often made in correspondence with new methods, by scientists working on concrete problems with some degree of autonomy. Conversely, the algorithm of requirements in academic science stipulates the selection of the research method first. The development of methods is a special discipline, and who knows how long it is going to take – often many years. Governments and companies are more interested in fast results than the advancement of knowledge, even if it harms their practical interests in the long run. As a result, methods get applied mechanically, and novel methods are all too easily discarded.

Studying the unknown is an experimental process without guarantees of what will emerge or when. Yet science today is carried out according to strict timetables, of political, academic or corporate origin. If a scientist has to spend two years just to develop a method to conduct a study, after two years he might become uninterested in doing the actual research or if he developed the method God forbid one day earlier, what then? If on the other hand the process is delayed, scientists are under pressure to rush the work, publish preliminary findings as established facts, or even falsify their research to meet the deadline. Good examples of this are states such as Russia, where scientific discoveries, according to newly approved legislation, must be made on time, that is according to the schedule. But scientific discoveries are not made on the schedule; alas, Russian leadership believes that this is possible, as if saying: we should strive for discoveries on schedule… Of course, you can make a discovery earlier, but keep it secret, wait until the 5th of the month, and present a report, simulate, so to speak.

Modern academic science at its core is a rather strange assemblage, which has heterogeneous categories, on the one hand, and disparate scientists, on the other. Most scientists are products of the order, establishment and society where they live. They bring into their science the usual traits such as self-branding, bullshitting, attentive stress and public relations focus, which are widespread in the surrounding society and have come to be rewarded in academia. At the same time as being supposed experts, they are just the way everybody else is and simply replicate science to serve the consumer society in which we live. They formulate scientific claims in the manner others design consumer goods: for saleability, not accuracy. If we speak about Baudrillard’s philosophy, his focus is on the “mass” that boils down to one individual. And the second focus of his attention is academic science, which is in fact nothing but a paradoxical structure within consumer society. Despite all of the assets of humanity (supposedly to some extent false ones), with all of their tools of research and the possibility to create new methods and much more, modern academic science functions according to rules that make it hard or even impossible to do all of this. Science is constrained by “common sense”, institutional rigidity, peer pressure and corporate and political issues.

For this reason, Baudrillard is highly insightful, as he has found the strength to oppose himself not only against mankind, to the society in which we live now, but also against academic science, allowing him to serve as a precursor for a future science; as Galileo did. Opposing academic science may be even harder than opposing “society”, since the former will necessarily take Baudrillard’s work and opposition to it into account, whereas the latter may simply ignore him. Baudrillard threatens to expose the skeletons in the closet of modern academic science: its irrational structure resulting from its complicity in consumer society. Figuratively speaking, those skeletons can be compared to a “dead pharaoh” who is worshipped, another figure in the model of God to whom agency is alienated.

There is a huge difference between modern science and the science which supposedly preceded the current one. The earlier science was objective and designed on practical experience on the basis of the key skill of the era (as termed by the academician G.S.Popov). Humanity in different eras has the concept of a “key skill.” As an example, in the middle ages, a key skill was the ability to handle a weapon to survive and the science of the particular era was built around that vital necessity. It also had some degree of autonomy, and thus contributed to further development of the skill.

For the first time in the history of science, at some point after World War II, it began serving society and as a result of which scientists stopped being scientists. Academics have become a kind of “operating personnel of tradition”, a variety of the manager or bureaucrat plugged into the administration of consumer society, rather than artisans of crafts or pioneers of knowledge. The distinctiveness of schools or universities as spaces related to knowledge began to disappear, as both became increasingly similar to factories, offices or supermarkets. The main aspect of science – applied science (a practical aspect of science, aiming to improve people’s lives) – has disappeared; there is academic science and there is mere application. Consequently, science has found itself as one of the armaments of capital. Capitalists have always been implicitly interested in gaining an advantage over others as competition in capitalist economies never stop. Knowledge has never been more freely available, nor more constrained in its application. This leads to a kind of paradox of negative freedom. Each individual has freedom in consumer society: he can study what he wants, where and when he wants, but the whole problem is that he does not want to because he does not need it.

Without constant development of applied scientific knowledge, the learning of science also falls into crisis. The classical/liberal system of upbringing and education has disappeared, yet teachers and academics retain professional authority based on this older system, which is also paradoxical. In today’s world, some even confuse a teacher with a scientist. The vast majority of professors at universities are not scientists, they are teachers. Bad? Good? Different. Formerly, a scientist used to teach because of necessity, but today it is the opposite: a pedagogue is a “scientist” by necessity. Academics engage in mediocre scholarship as a necessity for keeping their jobs, which are principally teaching and administrative jobs, and they often teach and administer topics in which their academic knowledge is very limited. As a matter of fact, academic science in the current form is almost useless. No-one pays it much attention, even the academics. That’s the paradox. After all, if it is a science, it has to be useful, but the facts confirm the opposite . Everyone in academia knows other academics are publishing shoddy, repetitive or workmanlike research, citing each other for mutual advantage without actually engaging with each other’s papers, redefining concepts for personal advantage, and so on; everyone knows that no more than a handful of people will read a given article, and that its central claims, unless they tread on someone’s toes, will never actually be tested, applied or criticised. Yet they keep up the game of simulating science, producing something which looks and internally functions very much like an integrated body of knowledge.

Since academic knowledge is no longer connected to applications, there is no way to distinguish between good and bad knowledge. Academic sciences become dependent on fashions, which are set by people whose scientific ability and knowledge are often questionable. Let’s consider as an example, “adaptive thinking” by the German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer (director Emeritus of the Center for Adaptive Behavior and Cognition (ABC) at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and director of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy). His research smashes the approach of modern science and mathematics. He demonstrates “adaptive thinking” throughout the book too: great abilities in the field of higher mathematics, using Bayesian and other models. Gigerenzer says that today humanity elevates man above all. For example, a machinist in a factory allegedly has to be able to keep triple integrals in his mind or a McDonald’s manager should calculate probability by means of a Bayesian model if humanity elevates man to the level of perfection. Such properties are frankly incredible; it is doubtful whether such functionaries have even heard of the Bayesian model. Nevertheless, people live without science, they are used to living this way and it seems totally fine in a consumer society. Instead of science, there is, for example, intuition, but the way it works or what it is, is not even interesting to an average person. For an average person “using” intuition is all about his or her sensations, the whole range of feelings and emotions, which periodically take a certain form; one attempts to decipher this form, calling it “intuition”, but this mystifies rather than reveals the forces producing such reactions. Yet a person who does not “intuit” in the expected way is an outcast. As Baudrillard said, today ignorance is the basis of social adaptation. Currently, social inclusion is based on a condition of inferiority and deficiency which is the foundation of life in the society of consumption. Inferiority is a mark of status: the more inferior you are, the more society owes you.

I am not trying to argue against support for people who are genuinely vulnerable: poor people, disabled people, children, and so on. Society needs to take responsibility for supporting these groups. Rather, I am criticising the trend to demand that ordinary, healthy, and “happy” individuals must either claim or simulate inferiority to gain recognition, rather than exercising agency, power, knowledge, productivity, and commitment to the degree that they can. When a perfectly healthy individual, who is not deprived of anything psychologically or physiologically, becomes inferior in order to gain as much as possible from this society, the result is a disaster, no matter how politically problematic this claim may sound. A point is reached where one must pretend to provide such configuration parameters to live well in society, and where the pretence becomes so ingrained that people actually become less than they could be. Imagine that everyone has to play the role of a disabled person in everything, all the time. Suppose, however, that this is not just faking, but produces the real effect of incapacity. As Baudrillard observes in Simulacra and Simulation: “Whoever fakes an illness can simply stay in bed and make everyone believe he is ill. Whoever simulates an illness produces in himself some of the symptoms”.[3]

Today’s situation resembles that found in The Adventures of Buratino (1976), a Soviet musical movie for children. (The screen version of a popular novel by Aleksey Tolstoy. A wooden boy Buratino tries to find his place in life. He befriends toys from a toy theater owned by the evil Karabas-Barabas, gets tricked by Alice the Fox and Basilio the Cat and finally discovers the mystery of a golden key given to him by the kind Tortila the Tortoise.) This movie gives a vivid example of that “country of fools”. Buratino, a Pinocchio variant, sells his textbooks and his chance at knowledge to go to a puppet show, only to be targeted for destruction by the show’s owner because he disrupts the show. He spends most of the movie trying to free the children forced to perform in the show. What is happening today results from inverted scientific concepts, which are, in fact, the paradoxes of this world. Another example of such a paradox: for some reason modern psychology considers it to be “normal” that masses of people go to work and every month or every week wait for their paychecks—indeed, the neoclassical economics prevalent in academic economics departments and the proliferating business studies and management studies departments take this for granted and aggressively encourage “job creation”; but the same business people who pay workers’ wages are considered in other social science disciplines such as psychology and cultural studies to be “pathological”. There are quite a lot of scientists who hysterically try to prove this. But how can those who provide the living of the “normal” be “abnormal”? Surely either the entire system is “normal”, or the entire system is “abnormal”? Another similar example is neuroscientific theories which are popularized today, often as a convenient way to justify things as they cannot be verified by experiments. Anyone can formulate a neurological or an evolutionary psychological hypothesis and present it as scientific fact. The actual development of neuroscience is still in its infancy and its findings change all of the time; most of which are uncertain and have few social or political implications, and quite a few take the form of “proving” things which are already known (that sadists enjoy others’ pain or impulsive people have lower self-control for example). Yet these findings appear in the media as if they are the height of verified scientific knowledge, and denying them is like denying gravity. The ancients suggested that “everything is comprehended through a demonstration,” but modern science does not want to demonstrate anything. It’s just there, that’s all (Generally, experimental research is still valued, hence e.g. “evidence based policy”; the problem is that the “evidence” is very narrowly constructed and of dubious quality). Up to a certain point, science used to demonstrate certain things to the world community. For example, it fired rockets into space, built rockets, invented computers, and so on. Most of the major scientific discoveries prevalent in the postmodern world were made between the 1930s and 1950s, and have only been incrementally improved since. The last irrefutable and real scientists lived between 1984 and 1986, but even in those years, they were already at the stage of leaving science because of their age. Some of their students continued their legacy, but very few of them. Some of these scientists, as such, can still be seen today, for instance, in cognitive psychology, Gerd Gigerenzer, Daniel Kahneman and several others. They are not young men anymore,they do not care about what “people think” and they say what they believe to be true. Even if many people do not agree with their work, these people still have no choice but to acknowledge the works of authority figures in their own fields.

However, the further progress of science has largely stopped. Science stopped needing to make discoveries, instead maintaining that “everything is already known” and “don’t revise, challenge, examine institutionalized things” as it may question the activities of previous scientists. Any new scientific discovery could question the scientific “discoveries” of others, which will expose skeletons in the cupboard. Academic gatekeeping and bureaucratic management of research are used to ensure that science remains within the bounds of orthodoxy, endlessly reaffirming what is already believed.

There is another extremely interesting regularity: the majority of scientific work that exists today is not demanded by anyone. Academic science and society exist separately: society is not interested in what academic science is doing, and nobody even pays attention to it. At the same time, academic science does not pay attention to society. However, it cannot go on like this very long. Certainly, society at all times was in need of science, but not the kind available today. To put it very simply, a modern scientist who did his last scientific work (good, bad, simulative) 30 years ago would still be considered a “scientist” in this society even if he had not done anything in the last 30 years, and only lectured at university. Once he received his PhD or Doctorate status, he was established as a scientist for some. This is what was criticized by Jean Baudrillard: the approach taken by modern science is mediocre. Yet paradoxically, everything necessary for the existence of high-quality science is available. There is no prohibition on methods and methodologies of science and research, as there was in the times of the Inquisition and the prohibition of certain claims in Europe. Everything is available, but the data and methods are not used. And most importantly, there is no desire among academics to be a true scientist, as the assessment criteria have become totally different. There are structural deterrents to original research. Consider the situation when a scientist deals with a certain subject that is not looked into by other scientists: there might be one or two other people who also research that subject. When such a scientist writes a scientific paper on the results of his research and sends it to a peer-reviewed scientific journal, he is asked: “Why is your citation index so low?”, to which he answers: “Well, who would cite me if there are almost no scientists dealing with the same problem?”. The journal might decide the work is too parochial to be published; alternatively, if it contradicts the previous claims of one of the reviewers, they might reject it on spurious grounds, or demand extensive revisions to bring it back in line with orthodoxy. Alas, the established paradigm followed in the academic world has its own assessment standards which are not conducive to scientific research, and which instead encourage simulation, circular repetition and mutual reinforcement of existing beliefs.

Another paradoxical situation arose recently in the Netherlands at a conference about the problems of blind review in scientific journals indexed in SCOPUS and Web of Science. One of the prominent scholars in his area, who was a participant in the conference, stood up and asked: “Who would want to blind review my work? I am very curious about who is up to review my work?” Remember that he is a number one academician in his area. Yet he wonders whether anyone could actually review his work. The same problem arises today for many leading scholars. Who can review the works of Gerd Gigerenzer? It is like criticizing one of the founders of depth psychology: Leopold Szondi, or Sigmund Freud, or Carl Gustav Jung, for instance. A leading scholar can be cited, but not reviewed. These kinds of circumstances are clear evidence that the very approach of the modern academic system with the requirements of “who to cite, who to review” is dysfunctional in its essence. Who will quote whom? Imagine a genius scientist who is “forced” to make reference to incompetent experts in a particular subject, who have no relation to science. Unfortunately, today, the same norms are imposed on the entire scientific community. A scientist, of course, can refer to his predecessor, but only if he considers it to be relevant. However, if the subject of his study has never been tackled by anybody before him, where is the room for the scientific novelty that is expected in science, if one has to necessarily quote and refer to others? This, among other things, is the problem.

What is the core of the conflict between Baudrillard and the academic community? Science contributes to the worldview of an individual. In current conditions, Baudrillard divided this “worldview” into three parts: illusion (delusion), simulation, and hyperreality. Science can only contribute to this worldview if it itself promotes illusion, simulation and hyperreality. In fact, speaking about the fact that this is not a worldview, but a simulation. People living in consumer society can only handle simulated science.

An illusion is a “category” when we think that we know something, without actually knowing it. It is always about the superficial perception of the subject, which has long since become a regular foundation of our society. The main reason for widespread social illusions, misconceptions and delusions is the speed and acceleration of modern life. High-paced living creates conditions favoring superficiality. As an illustration, if someone has no time to read a two-volume manuscript, they might instead choose to watch a 10-minute YouTube video which “summarizes” the subject in question. However, they may find themselves interacting with others who have also watched the same summary, at which point, it no longer matters if the core of the book was summarized properly or not.

Another important aspect of simulated science is signified by the “like/dislike” formula so clearly articulated on social media. Real science has to be based on objective data about the world. Simulated science has evolved into a set of data that is supplied with the properties of sympathy or otherwise: “I do not like this figure because of my psychological trauma, I am distressed about anything related to the digit “2” …” For example, academics are now expected to repeat the same moralised terms when discussing particular topics, for reasons related to ethics or politics rather than objectivity. People are meant to “situate” themselves within a grid composed of algorithmic binaries, and not to produce scholarship which escapes from these binaries. In other cases, subjective perceptions are taken as “feedback”, indicating not just perceptions but attributes of (for example) a product or policy. Subjectively, while listening to many “scientists and scholars” today, I catch myself thinking about clinical norms. Supposed scholars often articulate what seems to me a psychopathological discourse with no relationship to reality. For example, one “reads” a text from one’s own preformed point of view, projects into it content which is absent or barely discernible, and presents this reading as if it were a scientific contribution to understanding the text. Can one not similarly say that every psychosis or neurosis entails “reading” the world through a fixed idea, and is thus equally deserving of scientific status?

Modern academia also teaches its scientists how to lie, justifying it by misusing works of predecessors, and this is another way simulation comes into play. Students learn to repeat the appropriate jargon, but do not learn what it means (if it ever meant anything). They learn to deploy signifiers as if they are buzzwords or marks of allegiance or status. The result is often indistinguishable from science to the untrained eye, yet has nothing to do with investigating the unknown. A well-grounded scheme that is not factual is a simulative scheme. It is confirmed that most scientists have no idea what they are dealing with, psychologists do not know the human psyche, and physicists do not know their units and values, except for a small number of people who are actually engaged in scientific activities. I have been in science for about 25 years, throughout this quarter of a century, I haven’t met many real scientists, although I have interacted with many supposed scientists. Paradoxically, real scientific status is a provision that requires serious sustenance, but this status is assigned to the most obedient, those who tick the boxes for academic jobs and citation metrics, and not to those who are actually engaged in research activities and who can prove their studies to the world scientific community. The category of “obedient scientist” is paradoxical by itself. A true scientist is a revolutionist in science: s/he discovers something new, something which was unknown, and is accountable to the data and not to others’ opinions. After all, the main function of science is to clarify the fields of the unknown. Baudrillard attempted to contrast himself with the stupidity and vulgarity of obedience in science.

The third element scrutinized by Baudrillard was the study of the systems (essentially the results) of what has happened. His work America is a study of the entirety of one of these systems, the state of American life. The aforementioned text is the result of Baudrillard’s study of an interaction with an individual, with a fairy-tale fool, and that very paradoxical science, the worldview imposed by the modern simulative method of science.

It is possible to say that science has made everything in the world incomprehensible. Science for an uneducated person can be, and often is, incomprehensible in detail, but at least when it comes to concepts, it must be clear and understandable. However, modern science is incomprehensible and obscure in all its manifestations. How was this “accomplished”? It is necessary for the scientist to speak in a completely foreign language, to use hundreds and thousands of unclear, complex terms in a minute so that no one understands what was meant or what was said. Furthermore, since humanity has developed a strange trait, what the Strugatsky brothers call the “toggle-switch of self-esteem”, nobody wants to look like a fool and publicly express that he has no idea what is going on. Therefore, it is easier for him to recognize incomprehensible as understandable and reliable rather than to look like an idiot. Hence, most people accept what is given to them not because they understand the essence, but because they don’t understand a thing.

The settled mode of thinking in the US is quite strange as Baudrillard wrote in America – like people from another realm, mostly very primitive. Since I have friends and partners living in the US, I frequently deal with this country, and I must confess that in the beginning for me with my European mindset, it was not easy to communicate with them. Even the structure and vocabulary of American English and the way it is used was very strange for me in the beginning. A language can show a lot about the way people act and the way they think (translator’s note: especially for somebody whose native language is Russian, these two languages are extremely divergent from each other and simply very different in their essence).

Also, there is another category of “scientists” who “adapt and transmit” works of scientists to the masses in such a way that by virtue of ignorance the masses do not understand what was being conveyed by people they have never heard of before. There is a new trend that public activists and speakers are perceived as public authorities, but in fact, are totally incompetent in what they courageously start doing. Nonetheless, these people are perceived by the public and the media as scientists and experts, and the scientific community is in no fit state to put any check on this. The list can go on and on. In a nutshell, the majority of people implicitly consider that learning, in the truest sense of the word, is simply ludicrous. Subsequently, social demands are designed correspondingly. A simple example from today are the requirements of tech giants and large corporations, what they want from employees is not knowledge but skill, it doesn’t matter how knowledgeable one is, the question is simply whether he can demonstrate results.

In today’s consumer society, there is little social value in being educated or learning anything in the true sense of these terms. It is not classy to be educated, and it is socially useless or even dangerous. Consumer society’s main “measuring tool” of well-being is money. Thus, if one has it, then one is fine, if not then things are bad. Many people think that it is very easy to actually earn money, that it is enough to transform your hobby into your job. Well, if this is true, perhaps it would be smart to learn what money is, how to make it, come up with ways of making money, research financial systems, etc. But people don’t do that either. Why? The reason is unknown. As a result, money and wealth are further mystified. These systems cannot be investigated without having a specific approach, methodology, and research tools. And Baudrillard did brilliantly when it came to this; his approaches are conceptual, his research judgments and models are impeccable, and the conclusions he reached are unquestionably verifiable. Various things related to Baudrillard’s conclusions are so remarkably apparent that it does not even require evidence, in some cases it would be enough for anybody to look around and see it for themselves. On the one hand, the study of interaction and models is extremely difficult from a research perspective, but today it is crucial. Studying the current state of affairs (things that are already formed) explains the causes of their emergence in the first place. For instance, it becomes clear why we ended up having something in the form of a “consumer society”, or an “economy of the sign”.

The fourth subject of Baudrillard’s study is mysticism, particularly European mysticism: Baudrillard’s question “What are you doing after the orgy?” is about mysticism – the future is unknown. However, Baudrillard examined the “future” by means of different approaches. He did not just study what would happen, but also the character of relationships between people in that future, i.e., what it might look like and why. Baudrillard goes beyond the world, and tries to reflect on what is beyond hyperreality. The philosopher spoke of the fact that the world is given to us to be destroyed, that it is not enough to create a new one. Where would the previous world go? This matter was well articulated by him in Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?

Immortality tends towards the primitive. In one of the interviews from the series “The Legacy of Baudrillard’s School” and in my study of the philosophy and sociology of Baudrillard, I spoke with Dr. Thierry Bardini and he said that the idea of moving back to immortality is a simplification. The paradox is that one can reach “immortality”, but at the cost of becoming primitive and losing all his characteristics and traits, in other words, ceasing to be human. The attempt to create a superhuman, which has long been sought after all over the world in the course of history, invariably leads to the creation of a subhuman being. It leads to historical dangers such as fascism. Science can be very dangerous by itself and if used for evil, it may cause catastrophic consequences.

Baudrillard’s mysticism is expressed in concepts such as seduction, virulence, fate and the conspiracy of art. At the center of the mystical conception, there is a transparent evil, which is not inferior at all. The sign (symbolism, symbolic component) for Jean Baudrillard is a multifaceted mystical category, which he uses multi-vectorially and variously to conduct research, draw conclusions and explain causality. On the basis of mysticism, Baudrillard has written the following works: Fatal Strategies, The Perfect Crime, Passwords and Radical Alterity. Some elements of this fifth part of his philosophy and its consequences can be considered prophetic.

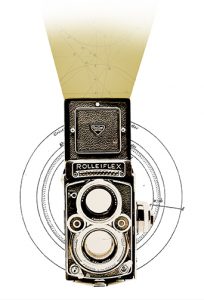

Apparently, one of Baudrillard’s verification test tools becomes photography (even though he used to say that photography is just a way to spend his leisure time). Human perception is structured in a way that an image is referenced to a concept. For example, a “pack of cigarettes” is both an image and a title (a signifier) that gives an understanding of what it is. At some point in time, in my view, Baudrillard started taking pictures so that the patterns he described could be understood properly. I believe that he went even further with this, he may have suggested the use of the camera as a research tool of philosophy and sociology, which creates an alternative to modern society and science. Baudrillard sees that with the help of a camera a person can look into the future. In one of his interviews with Nicholas Zurbrugg, Baudrillard draws a parallel between photography and writing: “I realized that there was a relation between the activity of theoretical writing, and the activity of photography, which at the beginning seemed utterly different to me. But in fact, it’s the same thing – it’s the same process of isolating something in a kind of empty space, and analyzing it within this space, rather than interpreting it.”[4]

Robert Capa, one of the founders of the world’s first photo agency, Magnum Photos, in 1947, once said that he can express more with three photographs than writing three books. When we think about Baudrillard as a photographer, it is possible to take his photographic works as a supplement to his writings. Therefore, studying the philosophical and sociological thought of Baudrillard while omitting his photography would not be enough to deeply understand his thought. In addition, it must be noted that Baudrillard was a very good teacher, like all sages. He did not present his system to people just like that, in a “naked” form, but split it throughout his books and essays by turning them into intellectual configurations. He then developed a building out of them, numbered every piece, every brick. Afterward, he dismantled (figuratively) the aforementioned house, put all of its components on the table and burned all of the schemes and sketches. This means that the situation turns out to be as follows. To understand the entirety of Baudrillard’s concepts and philosophical and sociological thought, one has no choice but to study every piece of his work, one must sketch the design of the building and try to assemble it from scratch. Thus, Baudrillard “doomed” the “student” to do an independent study on his works. Why is that? The French sociologist, Professor Lucien Oulahbib, explained to me that a true insight into Baudrillard’s thought with a thorough understanding of the models and schemes developed by him might become very dangerous in the wrong hands, and that Baudrillard probably feared that. Everything has two sides, the constructive and offensive, since Baudrillard’s philosophy and sociology are very much practical, their power can be exercised in the bad sense of the word.

One professor said that “Baudrillard is great for attacking any system, anything… it is a terrific hammer”. The philosophy and sociology of Baudrillard do have a “sacred sphere” inside of them which has a variety of practical systems. I have conducted an experiment and seen the result; on the basis of Baudrillard’s philosophy I was able to create “Security in the 21st Century Textbook”. Certainly, I already had extensive experience in this area as I have been engaged in related research for 10 years, but Baudrillard’s philosophy allowed me to clarify the situation and to create a firm framework for systematization relevant to current time.

In addition to all of the above, the philosophy and sociology of Jean Baudrillard are multidimensional, by using it, one can do “miracles”. That is, it is equally useful for a businessman as it is for a student, equally useful to both the military and a doctor. It could be helpful to anybody regardless of their position and area of specialty. Provided, if one diligently and seriously approaches the topic, he or she will be able to accomplish a lot.

As a result, I was able to provide a design of the philosophy and sociology of Jean Baudrillard (see image below), by schematizing it on the board.

We have thus identified five parts of Baudrillard’s philosophy, and a sixth component which is an unknown practical part of this philosophy in the form of a dual sphere:

- An individual, with the possibility of scaling levels to the city, masses, scanned, silent majority

- Academic science

- The system of interaction between these actors, the results of their interaction in the form of society and other kinds of systems

- The center of the structure has a key point of transition from the present to the future – orgy – future – mysticism. (“What are you doing after the orgy?”)

- Mysticism (future)

- The camera as a research tool

- A dual sphere of interaction among each other, a place where practical designs of the present and future are directed. All this is arranged in a way that allows us to fully comprehend an exhaustive amount of practical (applied) knowledge in the present, and understand the knowledge of the future by means of independent work and study.

In fact, Baudrillard’s system carries a certain concealed knowledge, accessible only to those who carry out a thorough independent study of his texts which aims to perceive their core. Thus, Baudrillard has created not only philosophy and sociology but has also provided an impetus towards establishing a new academic school in psychology. Most importantly, he also created a system of independent work for an individual study that may result in an applied science of the present and the future.

Leaping ahead, I will say that I won’t limit myself with just one book on Baudrillard’s thought. Every book I write about his system will have its purpose, just the way this book does. The purpose of this book is to teach the reader how to study Baudrillard’s philosophy on their own, how to structure the reading in a way that while studying Baudrillard’s books you will be able to fill in the practical details of the present and future. Subsequent books are probably going to be about helping to understand particular details of Baudrillard’s system (for example, nuances when it comes to the topic of a single individual, masses, society, science, and systems that already exist). Perhaps at some point in time, every person will need to ask themselves the same question posed by Baudrillard: What are you doing after the orgy? The law of outrunning the growth of demands and a number of other predicted patterns of nature make human desires illimitable, and desires are further intensified by impatience. The masses want everything and they want it right now! And this desire generates the orgy, but obviously, there is no eternal orgy, so what happens when the orgy is over? This is a very serious philosophical, sociological and psychological question. If the question is looked at from all three perspectives (philosophical, sociological and psychological) it yields many conclusions that should be grasped. The orgy is the key to unhappiness and dissatisfaction with life. Baudrillard’s photography is a mirror of his mysticism, which is beyond the orgy, it is an unknown future. You can look ahead to the future, and not too far away, let’s say the day after tomorrow or 10 years ahead, but the further it is the worse it gets. This world can be seen as an orgy, in fact, that’s what’s happening right now.

For example, currently, the whole world is in quarantine because of COVID-19—it is an “orgy”, so what’s after that? Baudrillard’s mysticism has a direct answer to this question: there will be fatal consequences of fatal strategies. What exactly will be the consequences? One has to sit down and look into the matter, but there is no doubt that the consequences will be fatal. After an orgy, there are always fatal consequences, as is evident throughout history. How long can an orgy last? Historically they are short-lived, even if it lasts long enough in the view of people, to the history of mankind it is a drop in the ocean. All that takes place after the orgy is mystical, a consequence of fatal strategies.

For all that, the purpose of writing this book is to teach the reader how to study the philosophy of Baudrillard and to discover ways that will allow each reader to delve into the depths of his philosophy and make the best out of it.

Notes

[1] Clarke, D. B., & Smith, R. G. (2017). Jean Baudrillard: The Disappearance of Culture: Uncollected Interviews (1st ed.). Edinburgh University Press.

[2] Smith, R. G., & Clarke, D. B. (2015). Jean Baudrillard: From Hyperreality to Disappearance: Uncollected Interviews (1st ed.). Edinburgh University Press.

[3] Baudrillard, J., Glaser, S. F., & University of Michigan Press. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation. Amsterdam University Press.

[4] Baudrillard, J., Glaser, S. F., & University of Michigan Press. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation. Amsterdam University Press.

Download Book “MAESTRO. JEAN BAUDRILLARD”