Douglas Kellner

Oakland, PSA, April 2007[i]

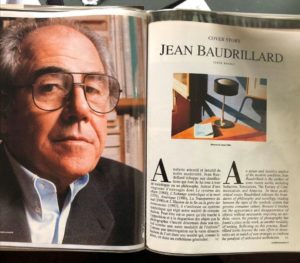

When asked to contribute to this forum on art and sociology I was working on a paper on Baudrillard and his book The Conspiracy of art, a collection of essays of recent work on contemporary art, and on a book Art and Liberation, the fourth volume of Collected Writings of Herbert Marcuse that I’m editing for Routledge, and after some reflection decided to compare both theorists for this presentation; to some extent Baudrillard and Marcuse represent antithetical positions on the potential of art to aide human emancipation in the contemporary moment so I’ll briefly play them off against each other and then comment on how they both contribute to in different ways to the sociology of art in the contemporary epoch.

To begin with Baudrillard: In the interview “Game with Vestiges” (1984), Baudrillard claims that in the sphere of art every possible artistic form and every possible function of art has been exhausted. Furthermore, against Benjamin, Adorno and other cultural revolutionaries, Baudrillard argues that art has lost its critical and negative function. Art and theory for Baudrillard became a “playing with the pieces” of the tradition, a “game with vestiges” of the past, through recombining and playing with the forms already produced.

From the late 1980s into the 1990s, Baudrillard sharpened his critique of the institution of art and contemporary art. In The Transparency of Evil (1994), Baudrillard continued his speculations on the end of art and transaesthetics, projecting a vision of the end of art somewhat different from traditional theories that posit the exhaustion of artistic creativity, or a situation where everything has been done and there is nothing new to do. Baudrillard maintains both of these points, to be sure, but the weight of his argument rests rather on a metaphysical vision of the contemporary era in which art has penetrated all spheres of existence, in which the dreams of the artistic avant-garde for art to inform life have been realized. Yet, in Baudrillard’s vision, with the (ironical) realization of art in everyday life, art itself as a separate and transcendent phenomenon has disappeared.

Baudrillard calls this situation “transaesthetics” which he relates to similar phenomena of “transpolitics,” “transsexuality,” and “transeconomics,” in which everything becomes aesthetic, political, sexual, and economic, so that these domains, like art, lose their specificity, their boundaries, their distinctness. The result is a confused and imploded condition where there are no more criteria of value, of judgment, of taste, and the function of the normative thus collapses in a morass of indifference and inertia. And so, although Baudrillard sees art proliferating everywhere, and writes in The Transparency of Evil that “talk about Art is increasing even more rapidly” (1994, p. 14), the power of art — of art as adventure, art as negation of reality, art as redeeming illusion, art as another dimension and so on — has disappeared. Art is everywhere but there “are no more fundamental rules” to differentiate art from other objects and “no more criteria of judgment or of pleasure” (1994, p. 14). For Baudrillard, contemporary individuals are indifferent toward taste and manifest only distaste: “tastes are determinate no longer” (1994, p. 72).

And yet as a proliferation of images, of form, of line, of color, of design, art is more fundamental then ever to the contemporary social order: “our society has given rise to a general aestheticization: all forms of culture — not excluding anti-cultural ones — are promoted and all models of representation and anti-representation are taken on board” (p. 16). Thus Baudrillard concludes that: “It is often said that the West’s great undertaking is the commercialization of the whole world, the hitching of the fate of everything to the fate of the commodity. That great undertaking will turn out rather to have been the aestheticization of the whole world — its cosmopolitan spectacularization, its transformation into images, its semiological organization” (1994, p. 16).

In the postmodern media and consumer society, everything becomes an image, a sign, a spectacle, and a transaesthetic object. This “materialization of aesthetics” is accompanied by a desperate attempt to simulate art, to replicate and mix previous artistic forms and styles, and to produce ever more images and artistic objects. But this “dizzying eclecticism” of forms and pleasures produces a situation in which art is no longer art in classical or modernist senses, but is merely image, artifact, object, simulation, or commodity Baudrillard is aware of increasingly exorbitant prices for art works, but takes this as evidence that art has become something else in the orbital hyperspace of value, an ecstasy of skyrocketing values in “a kind of space opera” (1994, p. 19).

The Art Conspiracy

Perhaps as a result of negative experiences with people exploiting his ideas for their own aesthetic practices and his own increasingly negative views of contemporary art, Baudrillard penned a sharp critique of the art world in a “The Conspiracy of Art,” published in the French journal Liberation (May 20, 1996) which is the center piece of his 2005 book with the same name that collects his most significant writings on art, and interviews concerning art, from the 1990s to the present.[ii] Baudrillard argues just as pornography exhibits the loss of desire in sex, and sexuality becomes “transsexuality” where everything is transparent and exhibited, so too has art “lost the desire for illusion and instead raises everything to aesthetic banality, becoming transaesthetic” (Baudrillard 2005, p. 25). Just as pornography” permeates all visual and televisual techniques” (ibid), so too does art appear everywhere and everything can be seen and exhibited as art: “Raising originality, banality and nullity to the level of values or even perverse aesthetic pleasure… Therein lies all the duplicity of contemporary art: asserting nullity, insignificance, meaninglessness, striving for nullity when already null and void” (Baudrillard 2005, p. 27).

Saying that art today is null can have several different meanings. Nullity describes an absence of value and Baudrillard could argue that because artistic value today is ruled by commercial value art nullifies itself. That is, on one hand, commercial value nullifies aesthetic value by reducing value to the cash nexus, thus aesthetic value is really ruled by the market, thus aesthetic values are collapsed into commercial ones.

Yet Baudrillard also wants to argue that art also historically has nullified itself as a transcendent aesthetic object, as something different from everyday life, by becoming part of everyday life, whether as found object in a museum, or by being ornamentation, or prestige value, in a home, corporation, or public space. Art could also be null because if aesthetic value is everywhere, it is nowhere, and has leaked out of its own aesthetic realm which, of course, museums, galleries, and the art establishment try to reestablish creating the illusion that art does exist as a separate and especially valuable realm. Thus, for Baudrillard contemporary art does not really create another world, it becomes part of this world, and thus is null in the sense of not producing aesthetic transcendence. In a later text “Art… Contemporary of Itself” ((2003) Baudrillard writes:

The adventure of modern art is over. Contemporary art is only contemporary of itself. It no longer transcends itself into the past or the future. Its only reality is its operation in real time and its confusion with this reality.

Northing differentiates it from technical, advertising, media and digital operations. There is no more transcendence, no more divergence, nothing from another scene: it is a reflective game with the contemporary world as it happens. This is why contemporary art is null and void: it and the world form a zero sum equation (Baudrillard 2005, p. 89).

Baudrillard goes on to indict the “shameful complicity shared by creators and consumers” and is especially put off by the discourses of the art world that continue to hype new artists, exhibits, retrospectives, as fundamental events of cultural importance. There is a “conspiracy of art” because at the moment of its disappearance, when art has simply disappeared into the existing world and everyday life, the art establishment conspires to hype it more and more with spectacular museum and gallery exhibits, record prices for art works at auctions, and a growing apparatus of publicity and discourse. The audience is part of this conspiracy, because it plays along, exhibiting interest in every new banality, insignificant new work or artist, and repetition of the past, thus participating in the fraud.

Now obviously, to make these claims, Baudrillard is operating with a very extravagant notion of what art should be and I’ve noticed tensions in his normative ideal of art. Some of his utterances seem to relate his normative concept to traditional concepts of avant-garde revolutionary art in which art is supposed to create another world, entry to an aesthetic dimension that transcends everyday life, and could even be an event which is a life-altering phenomenon, as in the passage I just cited above from “Art… Contemporary of Itself.”

Yet his ideal of art has twists and turns of its own. Some hints in the texts collected The Conspiracy of Art, however, indicate what ideal for art Baudrillard also has in mind. In a 1996 interview he distinguishes between aesthetic and form and notes: “I have no illusion, no belief, except in forms — reversibility, seduction or metamorphosis — but these forms are indestructible. This is not a vague belief, it is an act of faith, without which I would not do anything myself” (p. 59). For Baudrillard, his notion of form goes beyond Clive Bell and the Bloomsbury notion of significant form — which encodes aesthetic value, meaning, taste. Rather, for Baudrillard: “Art is a form. A form is something that does not exactly have a history, but a destiny. Art had a destiny but today, art has fallen into value, that can be bought sold, and exchanged. Forms, as forms, cannot be exchanged for something else, they can only be exchanged among themselves” (2005, 63).

Indeed, Baudrillard’s work on art translated in the 2005 collection reveals a primacy and mysticism of form, seeing truly life-altering art as: “Something that is beyond value and that I attempt to reach using a sort of emptiness in which the object or the event has a chance to circulate with maximum intensity” (2005: 71). The object or event “in its secret form” (ibid) are also described by him as surprising and unpredictable “singularities, forming an alterity and also serving as what he calls in another interview as a “strange attractor” (Baudrillard 2005, p. 79).

This could explain Baudrillard’s attraction to photography where the subject disappears and the object emerges in its strangeness as pure form, at least in Baudrillard’s ideal and imaginary of the art of photography.[iii] Yet Baudrillard claims that he is not interested in art as such but “as an object, from an anthropological point of view: the object, before any promotion of its aesthetic value, and what happens after” (2005, p. 61). This notion of the singularity of the object or event might explain why Baudrillard was so taken with the 9/11 terror attacks on the Twin Towers, since this was obviously a world historical event, but it was also an astounding aesthetic spectacle. Possibly Baudrillard secretly agreed with Karl-Heinz Stockhausen that 9/11 was one of the greatest acts of performance art ever, but could not say it since Stockhausen was so violently condemned for aestheticizing a major tragedy. I have argued before that the terror act of 2001 provided an event that shocked Baudrillard out of his world-weariness and cynicism and that has given much of his post-2001 work a compelling immediacy, sharp edge, and originality.[iv] Yet, quite frankly, the magnitude of the 9/11 event might have been so great that it confirmed his view that theory and art had no possibility of significantly capturing contemporary reality that was now going beyond any expectations, concepts, or representations. As Adorno asked, how can there be poetry after Auschwitz, Baudrillard might ask, how can there be art after 9/11?

The Conspiracy of Art enables us to strive for an overview of Baudrillard’s insights on art and what now appears as his anti-aesthetics.[v] In his collection of key essays on art, Baudrillard is more of a critic of art and a cultural metaphysician than an aesthetic theorist. He uses art to theorize general trends of contemporary society and culture, and to illustrate his metaphysical views and theoretical positions rather than analyzing art on its own terms or to do aesthetic theory a la Adorno or Marcuse.

While writing this paper I did the final copy-editing of a volume Herbert Marcuse, Art and Liberation which valorizes the aesthetic dimension and with Adorno could be read as the antipode to Baudrillard.[vi] I often find it useful to play off opposites against each other to see if I can find yet another position, or to test who do I really believe and agree with, in this case, the position of art in the contemporary world. In my aesthetic moments, I want to go with Marcuse and Adorno on this one, but in my darker theoretical moments I wonder if Baudrillard is not right, or is at least a needed antidote to excessive aestheticism.

Baudrillard thus emerges in my reading of his writings of the past decade as deeply anti-aesthetics in his current incarnation and a powerful critic of the contemporary art scene. Baudrillard is deadly serious, albeit ironic and sometimes playful, in condemning the contemporary art scene, appearing as what Nicholas Zurbrugg termed the “angel of extermination, yet he also appears as Zurbrugg’s “angel of annunciation,” blessing the perhaps hopeless attempt to find alternatives in art and theory in a fallen (i.e. imploded) world.[vii] Likewise, sometimes Baudrillard appears deeply reactionary, rejecting or eviscerating distinctive cultural phenomena of the present age, yet is at the same time highly radical, criticizing the very roots of contemporary cultural, political and theoretical pretension. He is at once a strong theorist and an anti-theorist, making reading and interpreting him a challenging enterprise.

I would argue that Baudrillard is his contradictions and anyone who tries to pin him down and offer one-sided interpretations fails. While there are, arguably, some threads and themes running through his work (the Object), there are certainly different stages of his work which Baudrillard sometimes lays out himself, but they are often hard to delineate, characterize, pin down, and are always subject to reversal.

Baudrillard is as well as a provocateur who often presents radical negations to his readers, as with his end of art and art conspiracy analysis, or his analysis of the disappearance of reality, the perfect crime, to which he alludes to at 2006 Swansea conference in his address “On Disappearance” (2006). As I’ve argued, Baudrillard’s work on art is especially challenging and provocative, quite original, and hard to sum up. But since reference to Duchamps and Warhol run through the texts of The Conspiracy of Art, and have long been Baudrillardian reference points, I’ll conclude by suggesting that Baudrillard is the Duchamps and Warhol of theory, mocking it by emptying it of messy content, deconstructing its problematic aspects by simulating it, putting on the audience by enigmatically repeating previous gestures and positions, but then making new ones that confound the critics. Although Duchamp, Warhol, and Baudrillard can often appear banal and repetitive, yet they often create something original and compelling, often with unpredictable effects. And so I conclude by evoking the triad of Duchamps, Warhol, and Baudrillard as objects, or strange attractors, of profound irony and provocation that continue to challenge our views of art, culture, and reality itself today.

It is relevant to note here that Baudrillard is appraising art today largely from a sociology of art perspective and finding art in contemporary society to be generally null for the reasons outlined in the book The Art Conspiracy. By contrast, Herbert Marcuse generally takes a more philosophical approach to art and aesthetics, although grounded in his critical theory of society and thus Marcuse too produces something like a sociology of art, which appraises the role of art in contemporary society.

Marcuse’s doctoral dissertation on The German Artist-Novel was rooted in Wilhelm Dilthey and the historicist school, reading the German Kunstlerroman from Goethe to Thomas Mann in the context of the developing German society of the modern epoch; in a sense, this is a sociology of art approach, but not a Marxian one such as would characterize George Lukacs’ Marxist works that situates, say, German literature in the context of the development of the German bourgeois and capitalism, whereas the early Marcuse had a more general sociological historicist perspective (and he was generally a critic of Lukacs’ Marxist approach as too reductive and occluding of the aesthetic dimension).

It is interesting that Marcuse had very different appraisals of art in its contemporary moment at different periods of his life; in his ultra-Marxist period when he began working with the Frankfurt School his essay “On Affirmative Culture” tended to critique bourgeois art as a vehicle of ideology and affirming the world as is, although he recognized that there were some utopian moments. In Eros and Civilization (1955), by contrast, that represented his most comprehensive perspectives on art and liberation, in his final book The Aesthetic Dimension, and in the papers I collected in the Routledge volume Art and Liberation, Marcuse had, by contrast, an extremely high evaluation of art’s potential for emancipation.

, great art contains a vision of a better world of freedom and happiness than the present one; and for Marcuse, the aesthetic dimension that preserves the otherness of art, its alternative ways of seeing, hearing, imagining, and so on, is different from the existing world by virtue of its aesthetic form. So if Baudrillard is right that there is no qualitatively different art with an aesthetic dimension other than advertising, media and consumer culture, and other cultural forms since for Baudrillard art has imploded into existing culture, society, architecture, fashion, politics and the economy -– if Baudrillard is right, then there is no aesthetic dimension today in Marcuse’s sense and no radical and emancipatory potential in art.

Marcuse famously finds the aesthetic dimension in the great works of the bourgeois tradition as well as the modernist avant garde tradition, and has been criticized by younger radicals for overvaluating classical bourgeois art and not seeing the radical potential in contemporary oppositional art. I once asked Fredric Jameson — a longtime friend and colleague of Marcuse and major contemporary Marxist aesthetic theorist — if he’d ever discussed postmodernism in any form with Marcuse (who died in 1979) and Jameson said no, he hadn’t and I never found anything on postmodernism by Marcuse in letters or texts, so we probably wouldn’t be able to have a discussion of contemporary art with those who think postmodernism is the dominant mode of culture and modernism is a thing of the past.

Still, I think we can use Marcuse’s notion of the aesthetic dimension to appraise different forms of contemporary art and do not myself believe that contemporary art is without value or emancipatory potential. However, I wonder if Baudrillard and Marcuse were sitting here today if they would totally disagree on contemporary art’s aestetic potential or agree that “Once upon a time art had oppositional potential, but today…”

Indeed, Baudrillard cryptically has a distinction between form and aesthetics and valorizes the former at the expense of the latter; Baudrillard has told interviewers that he appreciates as much as anyone the great classics of bourgeois culture, but apparently thinks that the form-creating capacity of artists is exhausted, although he valorizes form and events as such and has written that the 9/11 terror attacks are the only event of the contemporary era, although he has not aestheticized it as far as I know. Marcuse just might agree with Baudrillard that much contemporary art is null and void, lacking the aesthetic dimension that Marcuse thinks is the mark of great art.

Further, Baudrillard supposedly went to the Venice Biennale in the mid- 1990s and thought there was just too much art, it was too derivative and all cancelled each other out, with no really outstanding works. Possibly Marcuse would agree with that although I doubt he would be as totalizing, cynical, and perhaps ironic as Baudrillard. For Marcuse, art was far too important to make jokes or dismissive remarks about, while Baudrillard sometimes seems to scandalize for the sake of scandal, to make extreme statements, like all art is null and void today, for the sake of extreme statements, to be a provocateur and put deeply held views in question.

Also Marcuse was open to new art and like some forms of avant garde music, painting and the works of Bob Dylan; although when I queried him once about popular culture, he answered that the only film that had the aesthetic dimension in his sense was Eisenstein’s Potemkin and he was generally dismissive of the aesthetic potential of most popular culture[viii] — as was Baudrillard who is infamous for his theses of the implosion of meaning in the media.

So to conclude, although Baudrillard has perhaps the most radical critique and dismissal of art in the contemporary moment and Herbert Marcuse the most elevated and hopeful concept of the aesthetic dimension where there are visions and images of another world of freedom and happiness that can help emancipate individuals and even change society and culture, neither, I would argue, provide adequate perspectives for a sociology of art today that needs to contextualize and interpret, and appraise and evaluate, a wide spectrum of art ranging from so-called high art to so-called popular culture — or as I would prefer Media Culture. Both Baudrillard and Marcuse are too dismissive of the latter and so we have to go to theorists like Fredric Jameson or Ernst Bloch for a more robust critical sociology of art and aesthetic theory for the contemporary moment.

[i] This paper was presented as “Art and Society: Baudrillard vs. Marcuse,” Panel on Sociology and Aesthetics, Pacific Sociology Association, Oakland, March 2007. It is published here for the first time in the same form that it was presented at the conference.

[ii] After it was first published in Liberation in May 1996, the text appeared the next year as a pamphlet Le Complot de l’Arte (Paris: Sens & Tonka, 1997). It was collected in Screened Out which was published in English in 2002 and became the centerpiece and title of Baudrillard’s 2005 collection of writings on art.

[iii] On Baudrillard’s analyses and practices of photography, which go beyond the parameters of this presentation, see the material in Art and Artefact, edited by Nicholas Zurbrugg. London: Sage, 1997. There have also been many studies of his engagement with photography International Journal of Baudrillard Studies.

[iv] Douglas Kellner, “Baudrillard, Globalization and Terrorism: Some Comments on Recent Adventures of the Image and Spectacle on the Occasion of Baudrillard’s 75th Birthday,” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, Volume 2, Number 1 (January 2005) at http://www.ubishops.ca/baudrillardstudies/vol2_1/kellner.htm.

[v] Hal Foster titled his collection of writing on postmodern culture, one of the first and most influential in the postmodern debates of the 1980s as The Anti-aesthetic (Port Townsend WA: Bay Press, 1983). The collection included Baudrillard’s “Ecstasy of Communication” which I always took as signaling a radical postmodern break and rupture in history, signaled by his discourse of “No longer,” “no more,” “Now, however,” evoking throughout “this new state of things,” and yet some critics want to claim Baudrillard has nothing to do with the adventures of the postmodern…

[vi] See Herbert Marcuse, Art and Liberation, Collected Papers of Herbert Marcuse, Vol. IV. (forthcoming 2006), edited by Douglas Kellner. New York and London, Routledge and T. W. Adorno, Äesthetische Theorie (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1970), translated as Aesthetic Theory, by C. Lenhardt. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984.

[vii] See Nicholas Zurbrugg, “INTRODUCTION: ‘Just What Is It that Makes Baudrillard’s Ideas So Different, So Appealing?’” in Art and Artefact, op. cit., pp1ff.

[viii] I was told, however, that Marcuse enjoyed the 1970s TV cop show Kojak because it revealed that police were pigs, a sentiment that might echo with Black Lives Matter militants and those militating for social justice in the Great Global Uprising of 2020, still going on as I prepare this 2007 talk for publication.